Jaffa cakes were never my cup of tea. I always looked upon them with a slight side eye of disgust. However, I never openly acknowledge my displeasure for them. I just avoided them on biscuit plates in Mount Merrion or Bray.

Thinking back, I’m not sure what it was exactly but the combination of chocolate and orange has never sat comfortably in my mouth. Or perhaps, it was the fact that they reside somewhere in-between the space of a biscuit and a cake.

It was a thing that was not sure what it was and thus the texture stood in the middle of these two stanchions. Little did I know, the contested space of their name.

We often associate food with a particular identity and place it firmly in either/or categories. Perhaps, it’s just the way our brains work. We struggle with things that don’t firmly fall into singular spaces: like dual identities, we often distrust them as a position of falsity.

Jaffa cakes, which were first produced by McVitie’s in the UK in 1927, are a sort of hybrid between a cake and a biscuit. Though legally, and technically, they ‘are’ a cake—a distinction that became famous due to a tax case in the UK, where cakes are exempt from VAT, while biscuits are not.

But this isn’t the only betweenness that reside behind this sponge-like chocolate biscuit jelly jam cake. Jaffa cakes were named after Jaffa oranges after all and therein resides the rest of their story.

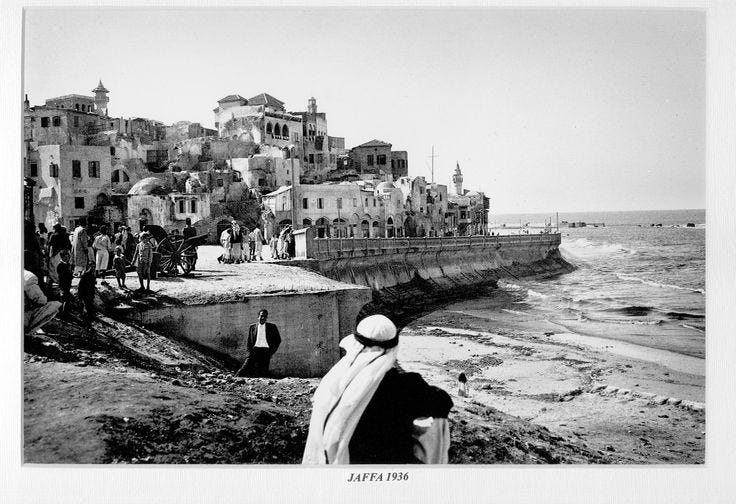

These sweet and seedless oranges were originally exported from Jaffa, a historic port city that is now part of Tel Aviv-Yafo in present-day Israel. These oranges, also known as Shamouti, became famous in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and were associated with the region of Palestine, which was then under Ottoman rule and later the British Mandate of Palestine.

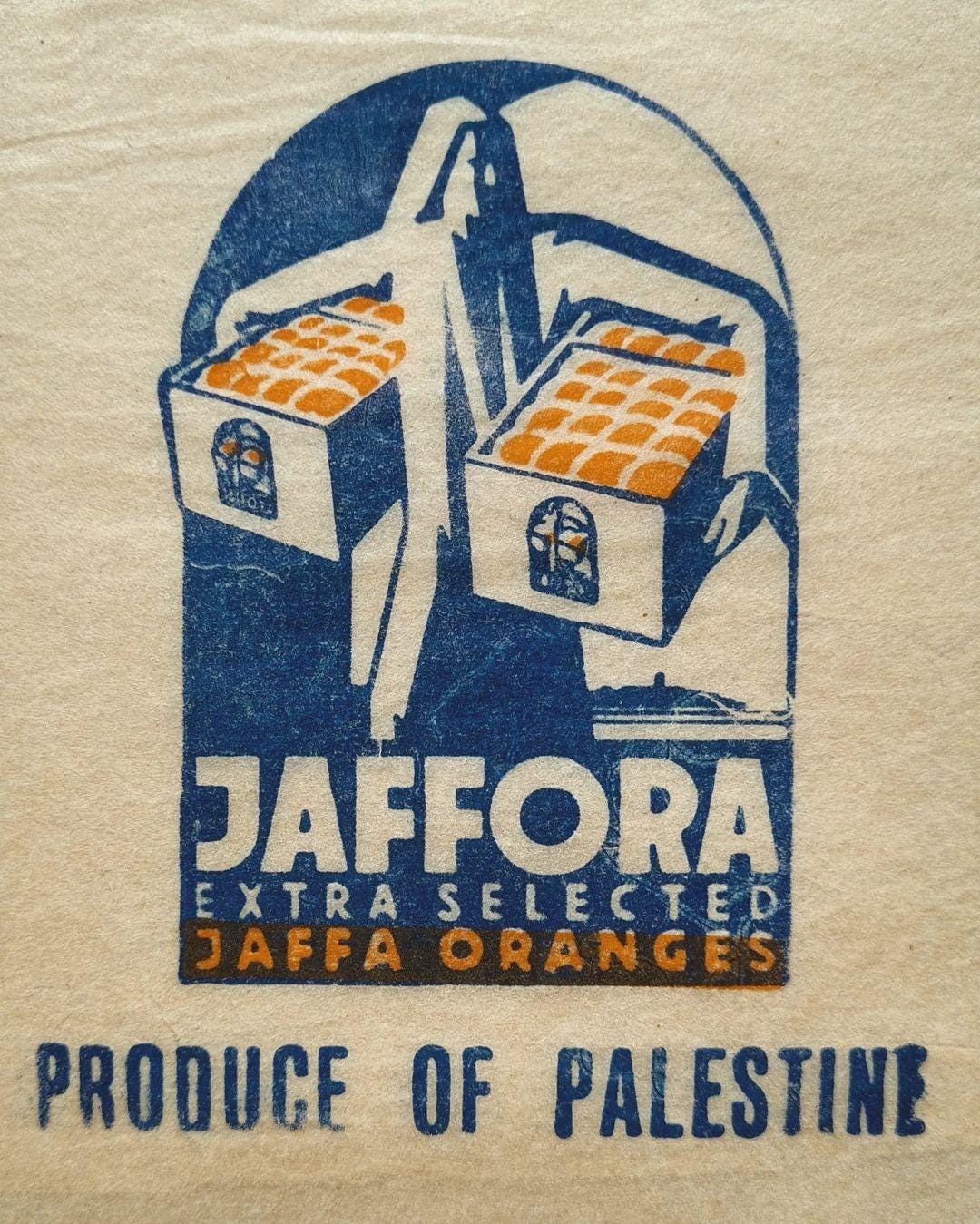

The choice of name by McVitie’s at the time was no accident. Jaffa oranges from Palestine were well known and loved in the UK during this interwar period and were often marketed as a sweet taste of the Eastern Mediterranean. The Empire Marketing Board’s campaigns in the 1920s (see poster below) had familiarized British people with Jaffa oranges and their links to these sun-kissed lands.

By invoking the name, McVitie’s tapped into a ready association of Jaffa with a rich, sweet orange flavour as well as an association with these biblical lands. According to McVitie’s own company history, the original Jaffa Cakes used a simple blend of sugar and tangerine oil to create the orange jam, and they explicitly named the product after the Jaffa oranges that inspired its zesty centre, not because they were using them, but because of what they evoked.

Despite this direct reference, McVitie’s did not publicize the geographic origins of the Jaffa orange itself. To biscuit and cake lovers, Jaffa simply signified a delicious orange taste. In fact, McVitie’s never trademarked the name Jaffa Cake, and this has allowed other companies to use the word Jaffa to describe any orange and chocolate treats.

As a result, in the UK and Ireland market, Jaffa grew into a generic descriptor for that flavour combination, further divorcing the term from its Palestinian roots. For decades, the packaging and advertising of McVitie’s Jaffa Cakes focused on their fun, chocolate-orange appeal, with no acknowledgment of Jaffa as a place in Palestine. It would have been the last thing on my grandparent’s lips in any case: politics and food just weren’t good bedfellows around the dining room table.

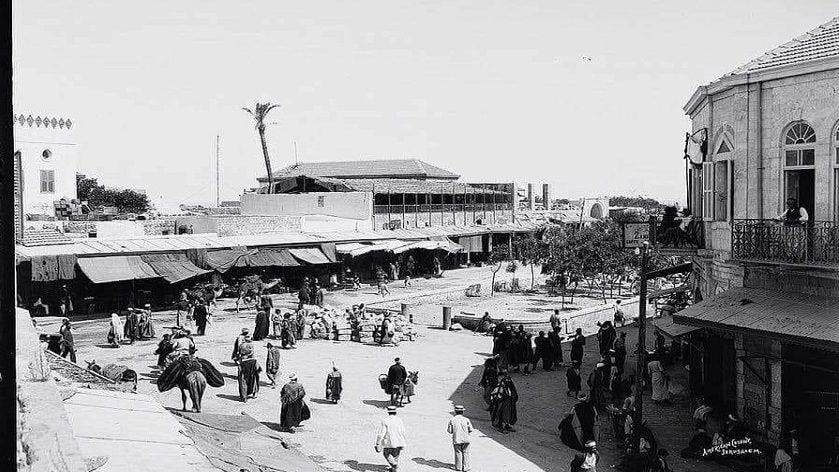

Many people are still unaware that Jaffa was a real city or that its name had anything to do with the history of Palestinian agriculture. Prior to 1948, Jaffa city itself was the cultural and economic heart of Palestine. The success of the orange trade was intertwined with Palestinian society. Families in Jaffa and surrounding villages cultivated citrus orchards, and the orange blossom and fruit became embedded in the local culture and identity.

Economically, the orange industry’s boom transformed Jaffa from a modest town into a thriving port city. As early as the 1850s, British consular reports noted these oranges from Jaffa’s ‘lush orchards’ making their way to Europe, were even reaching Queen Victoria’s table by the late 19th century. By the turn of the 20th century, citrus exports had become the leading sector of the Palestinian economy, far surpassing other crops. This laid the foundation for a legacy in which an orange was not just a fruit but a representation of Palestinian prosperity and cultural heritage.

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and the Nakba (catastrophe) for Palestinians, marked a turning point in the story of Jaffa and its oranges. Jaffa, the city, was designated for the Arab state in the UN’s partition plan, but during the war it came under heavy assault by Zionist forces. In April–May 1948, Jaffa was besieged and bombarded, leading to a mass exodus of its inhabitants by sea. Of 70,000 Palestinians who lived in Jaffa, only about 4,000–5,000 remained by mid-May 1948, the rest became refugees.

In the chaos, orange groves owned by Palestinians were seized. Under the new Israeli state’s Absentee Property laws, lands and orchards left behind by those who fled were deemed “abandoned assets” and confiscated by the state. Even some Palestinians who stayed found their property expropriated. Thus, virtually overnight, the thriving groves around Jaffa were taken out of their owners’ hands.

For Palestinians, the Jaffa orange quickly transformed from a symbol of pride to a symbol of loss. What had been a cherished emblem of their land and enterprise now served as a painful reminder of dispossession. After 1948, Palestinians would poetically invoke the orange as representing their ‘lost paradise’ – their homes, their orchards, and their way of life that they were forced to leave.

Palestinian historian Mustafa Kabha recounts that before 1948, the orange was so central that many imagined it on a future national flag. But after the Nakba, oranges came to signify the lost homeland in Palestinian collective memory.

Not surprisingly, the new State of Israel appropriated the Jaffa orange as its own national icon. Almost immediately, Israel’s citrus industry, built on the groves established by Palestinians began exporting under the brand name Jaffa.

In 1948, Jaffa was registered as a trademark by the Israeli Citrus marketing board. This board, originally formed under the British Mandate, now became an Israeli agency controlling all citrus exports – and it used the well-known Jaffa name to market the fruit worldwide.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Jaffa oranges became Israel’s flagship export and a cornerstone of its international image. Israeli promotional posters and brochures often featured orange orchards, presenting the success of the citrus industry as a triumph of the young nation’s ingenuity – while omitting the pre-1948 Palestinian role. Historian Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin notes that the Zionist movement deliberately adopted the orange as a symbol of the modernization of the land, despite citrus cultivation having predated their arrival.

The iconography of the orange helped perpetuate a myth that Palestine had been an uncultivated desert before, obscuring the reality of the vibrant Palestinian citrus culture that existed. Many came to think of the Jaffa orange purely as an Israeli product, unaware Palestinian farmers had cultivated it long before Israel’s founding.

In effect, the Palestinian connection was erased in global marketing. The term Jaffa on a crate of oranges or on a box of cakes carried a sense of quality and exotic citrus flavor, but not the story of its origin.

Over time, awareness of the true origin has begun to resurface. Still, for most of us, the use of name Jaffa remains apolitical with the focus on flavour or brand. In the UK and Ireland, McVitie’s continues to market Jaffa Cakes as a playful snack, emphasizing the orange taste but not its provenance.

The connection between Jaffa Cakes and Palestine is deeply rooted in the Jaffa orange. Culturally and historically, that orange was a Palestinian innovation and a source of pride. Agriculturally, it drove the economy of coastal Palestine under Ottoman and British rule and was renowned in international markets. Politically, its fate after 1948 turned it into a symbol of Palestinian loss and of Israeli nation-building, a dual identity that resonates in debates and boycotts to this day.

In terms of branding, the name Jaffa on a cake or an orange is a lasting, if often unrecognized, echo of this complex heritage. Every bite of a Jaffa Cake carries a small piece of Mediterranean history: the sweetness of a 19th-century Palestinian orchard and the story of a city called Jaffa that gave the world an orange and so much more.

Though it still won’t make me like them anymore, this history at least opens up the name of this cake to a wider audience.

From Jaffa, with love.

Jp.

Thank you for the interesting post, I had never really thought about Jaffa and was unaware of the history.

Super interesting! I never knew of the Jaffa cakes before visiting the UK. I went to Jaffa, once. I found it had the same vibes of Marseille, Tarifa, and Trapani.