Travel, sometimes necessary, often not, defines us as a species. We are constantly on the move, from place to place. Over the last 100,000 years we have come to inhabit nearly every space on the planet. Along with these travels, food accompanies us, ever by our side. Food migration happens naturally and often fuses with local or pre-existing traditions. So much so, that we often forget where the food came from, or the fact that it even travelled at all. There are numerous examples of this phenomena, but cheesecake is one of those things that is tied to various places (New York, Basque).

I have always been partial to cheesecake. In my early years, there was lemon cheesecake, all wobbly and bright. Then, in my teenage years they were made with white chocolate or baileys with shortbread bases. In my twenties, there was New York ones with a myriad of flavours, fruit glazes and different nutty biscuit bases. Finally, there were Basque cheesecakes with no bases when I first travelled to Spain in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

So many cheesecakes, so little time.

I could never turn down a cheesecake at the end of a meal, or even at the beginning.

Life was just too short.

Recently, on a trip to Copenhagen I experienced two wonderful Polish cheesecakes in Seks Bakery and Eatery, the first made with potato, the second topped with creme fraiche with had a lusciously creamy and buttery interior that completely stopped me in my morning tracks. I just had to eat it all, though I did savoury it slowly. However, when I asked Monica, one of the owners, what flavour it was, she responded:

This is only one of more than 100 different types of cheesecakes that I created that we don't reveal the ingredients that create the taste. And it's been many years like this now. We call it a secret cheesecake. Guests can guess them but till now only two of them did it correctly!

While we imagine cheesecakes to be a modern thing, they were originally made with curd in many European countries, including Ireland. Though initially a savoury cake made with fresh curd and lightly sweetened with honey, the introduction of sugar from the 16th century made this cheesecake turn a little sweet until they finally made it to America and became a full-on sugar bomb.

Ironically, many of the cakes that began in Europe return to us anew from the States, in a sort of inverted food migration. While this is not an altogether terrible thing (it’s just an effect of immigration and food travelling) we often forget the origins of our food.

There are several cheesecakes in Irish culinary manuscripts from the 18th century onwards. They were often called curd cakes and Catherine Hughes’ one from Tipperary in 1755 has a pastry base, sugar sweetened curds and is baked as were most original ones. The cheesecake from the Donovan Family Recipe Book (1713) contains currants, sack (a type of sherry), and some grated biscuit.

It was only later in the 20th century that the ‘no bake’ gelatine ones came to the fore with their smooth and silky texture often made with condensed milk, whipped cream, and set with gelatine.

In his book Historic Heston (Bloomsbury, 2013) British chef Heston Blumenthal argued that cheesecake was an English invention from the Middle Ages, because of its appearance in in Forme of Cury, an English cookbook from 1390. A version of cheesecake called a sambocade, made with elderflower and rose water, appears in the book.

However, its origins can be traced back to as far as Ancient Greece and Rome. The earliest mention arises in Cato the Elder's De Agri Cultura (On Farming) (c.160 BC). What is it with the British always trying to claim everything! Perhaps it’s an imperial thing!

For the Greeks, their earliest versions of cheesecake typically used fresh cheeses like ricotta, or a similar soft cheese made from goat's milk. These cheeses were mixed with honey and wheat, forming a basic but recognizable precursor to modern cheesecake.

When the Romans adopted and adapted the Greek cheesecake, they continued using cheese as a key ingredient. Roman cheesecakes used a form of cheese that was like ricotta, often mixed with honey and eggs. Cheese remained the primary ingredient in Roman versions, which is consistent with the dessert’s origins as a cheese-based dish.

As cheesecake spread through Europe during the Middle Ages, cheese was still the primary ingredient, although different regions began to experiment with several types of cheese. For example, in Italy, ricotta was commonly used, while in other parts of Europe, different soft cheeses were utilized. Medieval and Renaissance versions of cheesecake often contained spices and dried fruit, from sultanas to nutmeg. Dried fruit and spices pointed to luxury and gave the cake a symbolic capital amongst its eaters.

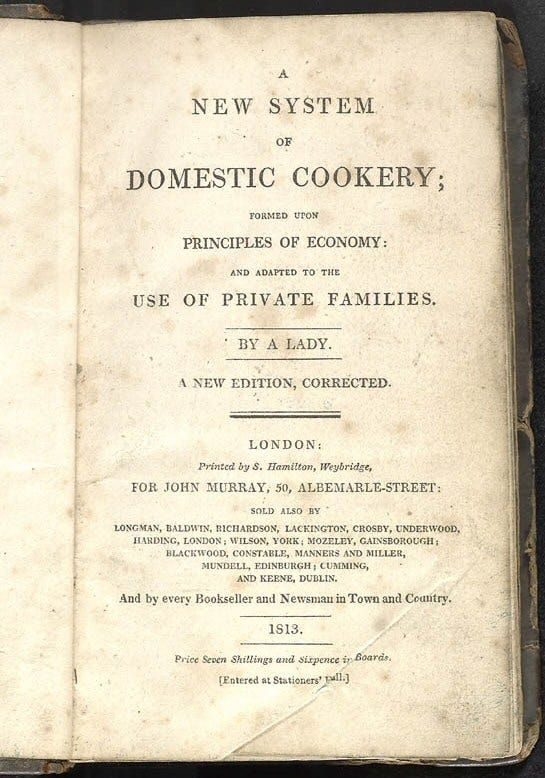

Early 19th-century cheesecake recipes in A New System of Domestic Cookery by Maria Rundell are made with cheese curd and fresh butter. Versions in her book are made with blanched almonds, eggs and cream, as well as including currants, brandy, raisin wine, nutmeg and orange flower water. By this stage spices and dried fruit no longer held the same status due to their ubiquitous nature in 19th century imperial England.

It wasn’t until the 20th century, especially in the United States, that use of cheese in cheesecakes became more refined. The introduction of cream cheese, particularly by James L. Kraft in the early 1900s (though cream cheese was developed from 1872 by William Lawerence), created the rich and creamy texture that we associate with modern cheesecake. The introduction of cream cheese gave rise to the iconic New York-style cheesecake, which remains one of the most popular varieties of cheesecake today, though some would say the Basque Cheesecake has eclipsed it (though both are baked, the New York one having a base and not being burnt).

As well as these two famous cheesecakes, there are a myriad of other around the world from Germany, Romania, Japan, and South Africa.

In truth, cheesecake is a vehicle for a food culture to demonstrate itself, in terms of its flavour identity. Nothing more. It cannot truly be linked to any one culture over another as some type of authentic food stuff. Meadowsweet or woodruff can be used to give a unique contemporary Irish taste to this ancient cake. However, an Irish cheesecake with saffron and almond flour would be just as appropriate but represent a different historical period of time in Ireland.

That’s the thing about flavours, they don’t just tie themselves to a particular country forever, even though we often imagine that they do. Flavours are historically linked to places and they often disappear with time. They are often forgotten. Their is no end point to flavour and identity, it continues to travel, like us, moving with migration. Imagine tracing the history of almonds in Ireland. What curious foodways might that reveal?

We may have moved beyond adding rosewater to our cheesecakes, but elderflower still rings true to our contemporary palettes. This is despite both these flavours arising from the medieval period as is demonstrated in Forme of Cury (1390), which incidentally is the one of the oldest cookery books from the UK and Ireland and the first to mention ingredients such as cloves, olive oil, and mace. Many recipes contain what were then rare spices, such as nutmeg, ginger, black pepper, cinnamon, and cardamom. Yet by the 19th this had changed. Spices were cheaper and more available.

So how do you like your cheesecake? Are you a baked or a no baked, a heavy set or a wobbly centre, a pristine white top, or a charred black one?

Until next time, and enjoy your cheesecake, wherever you find yourself.

Jp.

That’s a fascinating piece of writing thanks so much - I’ve made New York and the Basque style … I love them both … but I distinctly remember a lemon and lime cheesecake in Manchester some years ago… with a good coffee … it was delicious