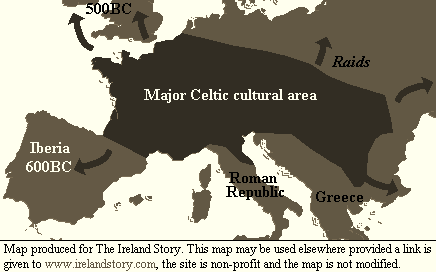

The Celts, who gradually began settling Ireland in small numbers from around the 5th century BCE, significantly influenced Ireland baking traditions through their agricultural practices, culinary innovations, and their vast knowledge of wild foods.

Their contributions laid the foundation for various aspects of Irish baking that have endured through the centuries. By the 300 BCE, La Tène-style artifacts appear (linked to continental Celtic cultures), and mark the influence of Celtic artistic and material culture on the island. It must be said that Celtic influence on Ireland was gradual and involved the blending of local traditions with Celtic cultural elements introduced through migration, trade, and communication with other parts of Europe.

The Celts were skilled farmers who cultivated several cereal crops in Ireland, including wheat, barley, and oats. These grains became staples in the Irish diet and were integral to early baking practices. As I observed in Part 1, the cultivation of oats led to the creation of simple rustic oatcakes, which many historians and archaeologists consider some of the earliest forms of bread in Gaelic Ireland. Oatcakes remain a traditional food in parts of Ireland today, especially in the North.

In the absence of modern leavening agents, the Celts developed methods to process and bake these grains in simple ways. They utilized grinding tools (quern stones) to mill the grains into coarse flour, which was then mixed with water to form dough. This dough was typically cooked on flat stones or griddles over open fires, resulting in flatbreads or oatcakes. These early baking techniques highlight the Celts' resourcefulness in utilizing available resources to create sustaining food staples. These techniques would persist in Irish culinary traditions for nearly two thousand years.

The Celts emphasis on using natural, wholesome ingredients and their methods of food preparation have left a lasting imprint on Irish cuisine. Their baking practices, centred around the use of whole grains and simple preparation methods, reflect a culinary philosophy that valued sustenance and simplicity. This approach was carried forward into modern Irish baking traditions, where breads like soda bread and scones, cakes and tarts, were cherished, not only for themselves but also as communal activities, which reinforced social bonds and shared food traditions.

As well as bring farmers, the Celtic peoples excelled at metalwork and with them came the introduction of pots and pans and tripods for cooking and baking. Many similar iron tripods are still used for cooking lamb and goats today, as well as baking in pots over an open fire. The Celts were a sophisticated society, and their diet was rich with wild foods, which undoubtedly made their way into the food stuffs that they baked. However, it’s difficult to assess at what level these wild foods made their way into their oat cakes and flat breads.

While we don't have direct evidence of specific combinations, archaeological finds and historical accounts suggest that wild foods played a significant role in Iron Age and early Celtic diets. The Celts had a deep knowledge of foraging and used wild plants in many aspects of their diet. Since bread was often simple, adding wild herbs, nuts, or berries would have provided extra nutrition and variety. Special flavoured breads may have been prepared for feasts, rituals, or as offerings. Below is a list of some possible wild food combinations that the Celts may have used in their breads.

Wild Herbs and Plants

Nettles (Urtica dioica) – High in nutrients, nettles could be dried, ground, or chopped and mixed into bread dough.

Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum) – Used for its strong flavour, like modern garlic bread.

Sorrel (Rumex acetosa) – Adds a lemony, tangy taste.

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis acetosella) – Offers a mild citrus-like flavour.

Chickweed (Stellaria media) – A mild, slightly sweet green.

Dandelion leaves – Could add a slightly bitter note, like chicory.

Nuts and Seeds

Hazelnuts – A staple of the Celtic diet, they could be ground into flour or added for texture and protein.

Acorns – If processed to remove tannins, they could be ground into flour and mixed with grains to make a more complex and nutritious bread. This is an arduous process.

Flaxseeds – Could be added for texture and nutrition.

Wild Fruits and Berries

Blackberries – Would have been a seasonal treat, added to bread for natural sweetness.

Bilberries (wild blueberries/Fraughans) – Small, sweet, and nutritious. Have a long history of use in Ireland.

Rowan berries – Slightly tart, but edible when cooked.

Hawthorn berries – Sometimes used in food and for medicinal purposes.

Seaweed and sea herbs

Seaweed – a multitude of seaweeds such as dillisk, sea lettuce and nori may have been used in breads, such as laverbread.1

Sea herbs – sea herbs could be chopped or ground down and added to a dough to provide vitamins, mineral and additional nutrition.

Honey and Sweeteners

Wild Honey – One of the most natural sweeteners available, likely used in special breads.

Tree Sap (Birch or Alder) – Could be boiled down into a primitive syrup. This is something that we still do today in the restaurant.

Fermented and Sour Ingredients

Sourdough Techniques – If wild yeasts were used (see discussion below), the bread could develop a natural tangy taste as well as a leavened aspect.

Malted Grains – Allowed to sprout before grinding, adding sweetness and improving digestibility.

Dairy and Animal Fats

Butter or Animal Fat (Dripping, Tallow, or Lard) – Adding richness and flavour.

Curds or Soft Cheeses – Possibly incorporated into breads for extra protein.

While the Celts had all this wild food at their disposal, so did the Bronze age and Neolithic peoples that inhabit Ireland, so they too may have made flavoured breads. We continue to make use of all this wild food (and more) in Aniar restaurant.

Food innovations of Celtic civilization in Ireland include thrown-wheel pottery as well as rotary stones for grinding wheat. A pair of large, decorated stones known as ‘beehive querns’ were used for grinding grains (Ó Cróinín, 2005). Many of these have been found in the northern half of the country (Caulfield, 1977) and they have been linked to the ‘dramatic expansion in agriculture’ around 300 CE. As with the earlier settlers, Celtic people also made butter and cheese, two food stuffs that would become part of the Irish baking tradition for centuries to come.

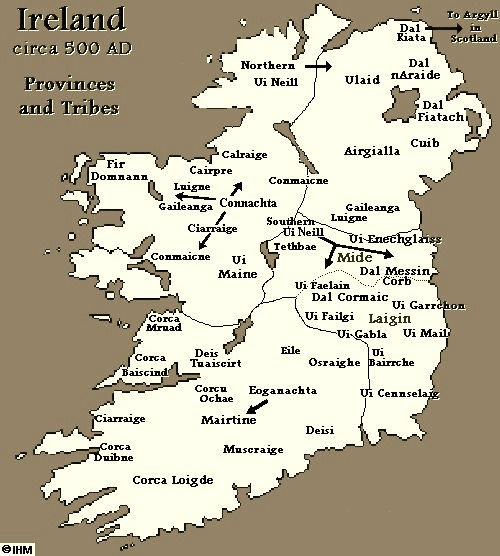

By the 5th century CE, Celtic people had thoroughly blended with the exiting indigenous cultures on the island. This resulted in the emergence of a Gaelic culture as well as the division of Ireland into kingdoms, such as, Tuisceart, Airgialla, Ulaid (Ulster), Mide (Meath), Laigin (Leinster), Mumhain (Munster), Cóiced Ol nEchmacht (Connacht).2 Despite subsequent invasions by the Vikings and the Normans, this Gaelic order would remain in place until the 17th century.

Before we move to the Christian era, it’s important to consider sourdough during this period. While I intimated above that the Celts may have produced sourdough, it is not clear at what stage baking leavened bread in Ireland began. An Irish legend tells us that a woman invented sourdough when she left a little of the remaining dough in her bowl and mixed fresh dough with it when she returned to bake (seemingly she was off ‘hunting’ with her lover). Another interesting method that Bríd Mahon mentions in Land of Milk and Honey (1991) was use of sowans (the juice of fermented oat husks) to create a starter culture to help the bread rise.

While there is no direct archaeological evidence of sourdough bread production in ancient Ireland, it is plausible that sourdough-style bread could have been made as early as the Neolithic period. The intentional and widespread use of sourdough techniques in Ireland likely depended on later influences from European bread-making traditions. Sourdough was never as prominent in Ireland as it was in regions like the Mediterranean or northern Europe, where it has a longer documented history.

However, sourdough is one of the oldest forms of leavened bread, relying on the natural fermentation of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. This process likely occurred accidentally when a mixture of flour and water was left exposed, allowing fermentation to begin. With the introduction of wheat and barley during the Neolithic, early farmers may have discovered basic fermentation methods, though evidence of intentional sourdough-making in this period is speculative. Increased trade with Europe (especially Rome and Greece), as well as those Celtic speaking people settling in Ireland from at least 500 BCE, means that the technology to make some type of basic or primitive sourdough may have been possible.

I hope you have enjoyed this little historical insight into baking in Ireland. I was going to include the Early Medieval (Gaelic) and Christian this week, but the Celts had more to say than I thought. More than a change in bread making method, the Celts brought about a change in technology which helped feed more people on the island.

For the first 8,000 years of life on Ireland, bread (and baking to a certain degree) remained similar. With the dawn of a new millennia, this would change as monasteries, equipped with rudimentary ovens, began to bake in ways that we still might recognise today.

Join me next week for the next episode when we’ll look at the Brehon laws, the links between bread and beer, early Christian Ireland and, hopefully, the Vikings.

Best, Jp.

Laverbread, or at least the practice of boiling and consuming laver seaweed, likely dates to prehistoric Ireland and Britain, but written records appear only from the 17th century onward. While it became most associated with Wales, it was almost certainly also made in Ireland for centuries, particularly in coastal communities. Given Ireland’s long coastline and reliance on foraged foods, laverbread or similar seaweed-based dishes would have been made in Ireland alongside its use in Wales.

The modern Irish provinces do not exactly match up with the boundary divisions of the older kingdoms.

![Ireland in 100AD [10kB] Ireland in 100AD [10kB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V7Ys!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F33ac0502-1a88-4dc2-b432-34cbceaebf5a_375x481.png)

Great read! Cooking vessel manufacture and the ability to control firing must have been major factors in the evolution of cooking and diet.

Fascinating thanks