Though Joyce did not actually create Bloomsday (the first was in 1954), he knew that by setting his monumental novel on a single day, that someone in the future may decide to celebrate him (and his novel) on that day. Even before the first celebration, friends of Joyce were gathering on that day. Harriet Shaw Weaver, Joyce's lifelong patron, wrote to him in 1924 to say that a small group had gathered in Dublin to join in honour of the book and its author.

But what has all this got to do with food, especially Irish food culture?

I suppose in less than seventy years, Bloomsday (celebrated every June 16th) has become a national and International Day of Joyce wherein people celebrate, directly and indirectly, Ireland, Irishness, and of course, the food that appears in the novel (as well as other foods of Edwardian Ireland).

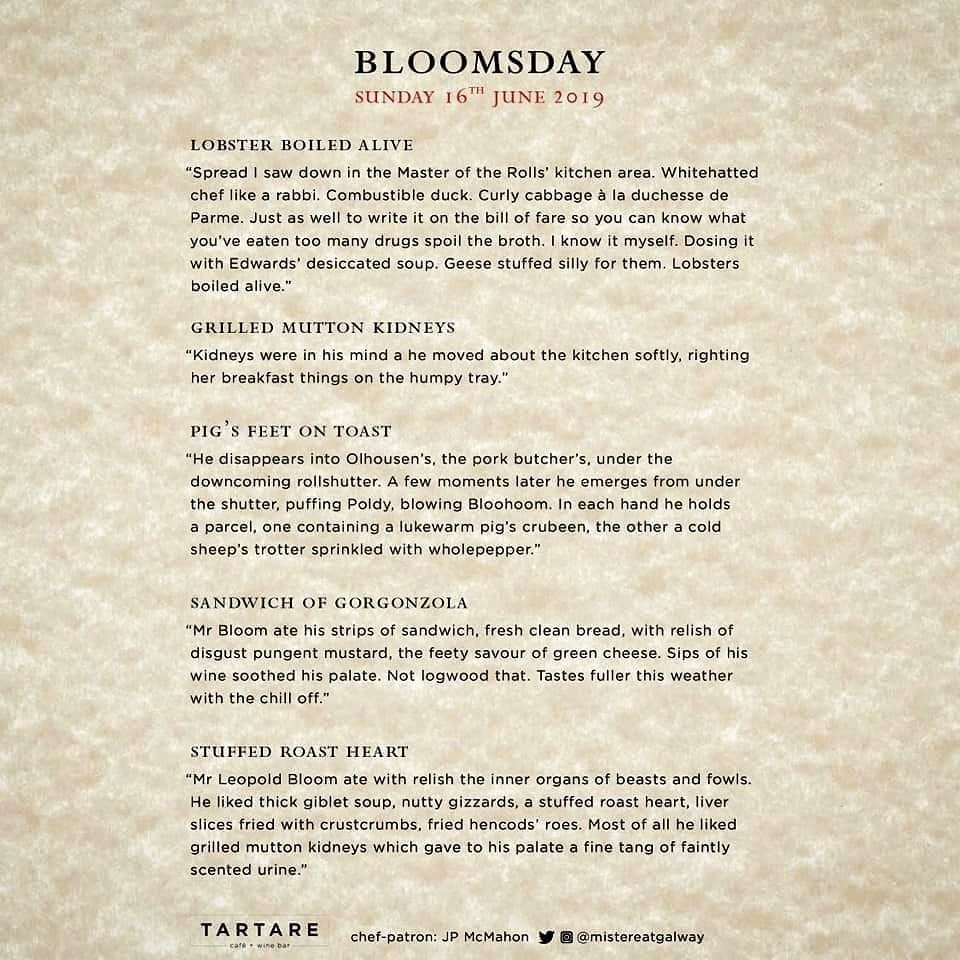

Bloomsday food celebrations usually consist of various food stuffs from, grilled kidneys:

“Mr. Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls... most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.”

– Ulysses, Episode 4 (Calypso)

To a Gorgonzola cheese and mustard sandwich, served with a glass of Burgundy wine, like Bloom had at Davy Byrne’s pub:

“He tore away half the loaf, propped it between his knees and, having pulled the pungent cheese, began to eat the greenish potted meat smeared with mustard.”

– Ulysses, Episode 8 (Lestrygonians)

To seedcake (with caraway seeds) which appears in the sensual memories of Molly Bloom, Leopold’s wife, and has become a symbolic Bloomsday dessert:

“...and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes... and I drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.”

– Ulysses, Episode 18 (Penelope)

There are many more food offerings in Ulysses and many pubs and contemporary restaurants offer Joycean tasting menus or Edwardian breakfasts, sometimes with period dress and readings. These often include dishes such as tripe and onions, Irish stew, pea soup, roast duck, pig’s head, Dublin coddle, fruit and sponge puddings, as well as plenty of stout, whiskey, Burgundy wine (as in Davy Byrne’s) and Earl Grey or breakfast tea. Many places draw on The Joyce of Cooking: Food & Drink from James Joyce’s Dublin by Alison Armstrong (New York: Station Hill Pres, 1986) which contains over two hundred recipes.

The food culture that surrounds Joyce’s novel and Bloomsday is simply outstanding, and it often makes me wonder why we don’t celebrate our food culture more often, for its own sake. Of course, they are various festivals, such as the Galway Oyster Festival, but with a reduction of funding for food festivals they are slowly disappearing from the many towns and cities of our island.

As I said, the first Bloomsday took place in 1954, marking the 50th anniversary of the day on which Ulysses is set. It was organized by Irish writers Patrick Kavanagh, Flann O’Brien (a.k.a. Brian O'Nolan), Anthony Cronin, and critic John Ryan (it also included Tom Joyce and writer and critic A.J. Leventhal.

They attempted to recreate Bloom’s journey across Dublin using horse-drawn carriages, though the expedition famously fell apart in drink and chaos before completion. I don’t think much food was eaten that day! It supposedly ended with a very drunk Flann O’Brien in The Bailey on Duke Street (if he even made it that far).

Ulysses is not the only book of Joyce’s that contains references to food. Food plays a deeply symbolic, sensual, and sometimes grotesque role in his other work, such as Dubliners (1914), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), and Finnegans Wake (1939) For Joyce, food is not just sustenance. It’s a lens to understand class, culture, memory, sexuality, religion, and our own identities.

Food is the most human of acts, eating, preparing, and sharing. Joyce uses it to ground his characters in the physical world, showing how their acts of eating (or absence) reveal their personalities. For Joyce, food also reveals social standing and cultural anxieties in Ireland under colonial pressure. In Dubliners, characters eat meager meals or attend awkward dinners that expose tensions. In the last story, “The Dead”, the Christmas dinner is a ritual of politeness masking the emotional repression of a different time.

Food becomes a battleground between Irish Catholic austerity and foreign temptation in Joyce’s work. Stephen Dedalus, in A Portrait of the Artist, rejects meat on religious fast days, but his longing is ever-present for this food. In Ulysses, Bloom’s mixed heritage (Jewish-Irish) plays out in his dietary habits: kosher echoes, pork kidneys, and an outsider’s gaze on Catholic Dublin’s traditions, especially when they involve food and drink.

Joyce often uses food metaphorically for erotic experience, focusing on the flesh, the mouth, the sweetness, and the messiness of food. Molly feeding Bloom seedcake from her mouth is a symbolic moment of mutual desire. In the “Lestrygonians” episode Bloom watches mouths eat, chews slowly, and contemplates the animality and beauty of digestion. Finally, Gerty MacDowell, associated with seaside sweets and perfume, becomes an object of Bloom’s masturbatory fantasy.

As well as the sexual, Joyce finds within food the grotesque and the comic. In Ulysses, bodily functions are never far away, such as urination, defecation, and flatulence. Joyce doesn’t just show us the biological side of digestion, but also the ridiculous and preposterous ways in which we think about it privately and publicly.

The events of Bloomsday often happen unbeknownst to many of us in the food world. Of course, this is due in part, to the difficultly, or the perceived difficulties, of Joyce’s writing. For many years we celebrated Bloomsday in our café and wine bar Tartare, and we even did a Joycean menu in Aniar to celebrate the year 1916 (in 2016).

As a lover of Joyce and Irish food culture, I hope the chasm that divides them is bridged, in much the same way we need to create a bridge between our arts and our food culture. We need to stop isolating our various industries, bringing them instead together, to add richness, storytelling, and performance to our food.

But more on that next week.

Jp.

16th June, 2025.

In the early 1980s when I lived on Lombard Street West in Dublin (where Leopold and Molly lived in fiction in the first years of their marriage) I emerged on Bloomsday to head to my summer job as a bus conductress. Two neighbours - one a journalist, the other an Elvis impersonator in full Vegas regalia - were grilling kidneys in the street. They slapped one between the halves of a soft, sweet, yellow bread roll and handed it to me. Not unpleasant. Rather surreal.

That sounds very surreal Valerie. Great article JP. I didn't realize there's such emphasis on food in Joyce's work. A lot of various kinds of meat dishes, probably of the cheaper variety in those times, no doubt 🤔