Irish food culture between 1801 and 1922 was shaped by economic hardship, colonial rule, agricultural practices, and great social changes. This period includes the devastating Great Famine [An Gorta Mór] (1845-1852), British policies that influenced Irish agriculture up until the present, Anglo-Irish dining, and the gradual modernization of food habits for the middle class through the industrialization of food production.

Truth be told, this period, more than any other period in Irish food history, is a tale of two sides. While divisions between the native Irish and the colonists existed during the previous centuries, the profound hardship of the 19th century acerbated the gulf between the two sides. Food plenty and food scarcity abounded simultaneously in Ireland throughout the century.

Before the Famine, the Irish diet was heavily dependent on the potato, particularly among the rural poor and native population. This was due to its high nutritional value, adaptability to the Irish climate, and ability to sustain large families on small plots of land.

The typical diet consisted the native Irish consisted of potatoes (the staple food, often eaten boiled with salt); buttermilk (an important protein source, often consumed with potatoes); oatmeal (used in porridge and bread), cabbage & root vegetables (grown in small kitchen gardens); pork & bacon (consumed occasionally by better-off farmers); seafood and seaweed (coastal communities ate fish, though it was less common inland).

Grain-based foods were grown for export rather than local consumption. Most native Irish people, particularly peasants, consumed little meat, as beef and wheat were primarily produced for British markets.

In contrast, the Anglo-Irish (Protestant landowning class of British descent) diet of the period had a distinct food culture that reflected their wealth, British influences, and access to high-quality ingredients. Unlike the primarily agrarian Irish Catholic population, who often lived on subsistence diets of potatoes, oats, and dairy, the Anglo-Irish elite enjoyed multi-course lavish dinners, fine meats, elaborate pastries, and imported wines, while their kitchens were run by servants producing both aristocratic and practical dishes. With a strong estate-based food system the wealthy enjoyed their position as landlords and upper-class citizens through food stability.

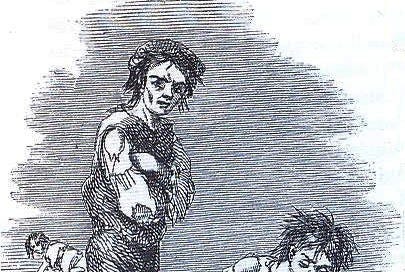

The Irish Potato Famine was caused by potato blight, which destroyed successive potato crops, leading to mass starvation, disease, and emigration (1847 was the worst year). The famine resulted in over one million deaths and mass emigration. The most severely affected areas were in the western and southern parts of Ireland. This is where the Irish language was dominant.

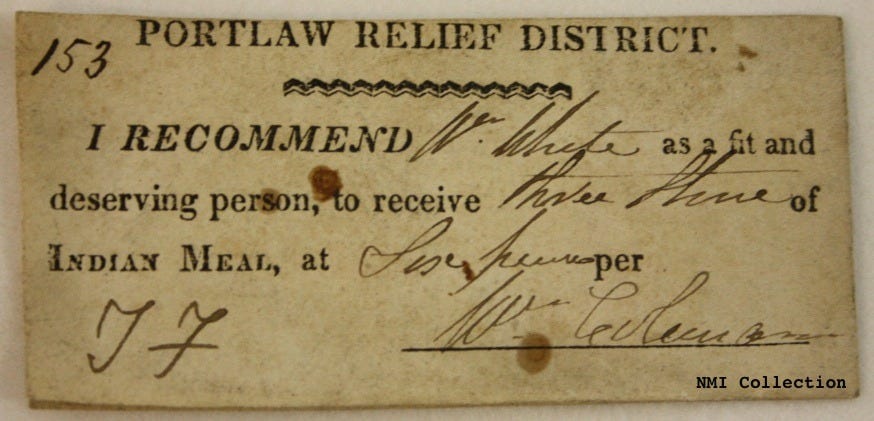

In Irish as, this period is called An Drochshaol (the bad life). During this period there was a shift in diet and a reliance on alternative crops like turnips, grains, and maize (imported by the British as famine relief). There was an increased dependence on tea and sugar, as famine survivors sought cheap, comforting calories. Soup kitchen were set up and indian meal bread became a staple among the starving poor.

The result of the famine was a decline in potato dependence, although it remained central, other foods gained importance. After the famine, cattle farming expanded, leading to a rise in dairy and beef production. However, much of this food was exported to Britain, reinforcing rural poverty.

In terms of baking, the period between 1801 and 1922 was heavily influenced by available ingredients, cooking methods, and social class. The period saw a shift from traditional hearth baking to more refined techniques with the introduction of ovens in wealthier households and urban bakeries. However, most rural homes relied on simple bread-making techniques that required minimal equipment.

Since wheat was often grown for export, oatmeal, barley, and later, soft wheat was more commonly used for domestic baking. Baking was mostly done on open hearths rather than in ovens, leading to distinctive methods like griddle baking and baking in a bastible pot.

One of the most iconic Irish breads, which emerged during this time was soda bread. It became popular after baking soda was introduced to Ireland in the 1830s. I am always asked why soda bread became so popular in Ireland. There are several reasons. Irish wheat was soft and low in gluten (due to harsh weather conditions), making it unsuitable for yeast-leavened bread. Soda and buttermilk provided an uncomplicated way to create a leavened bread without needing yeast. Before the advent of domestic ovens, it was typically baked in a bastible (a cast-iron pot with a lid, used over an open fire) or on a griddle.

As in previous centuries, oats were still popular in terms of baking. Oatcakes, made with oats, water, and sometimes buttermilk, were baked on griddles or stone slabs directly in the hearth. In the poorer households, oat-based bread was the staple before the potato became dominant. Brown bread, made with coarse wholemeal flour was popular among rural and urban populations and often eaten with butter or jam.

After the introduction of the potato, they were sometimes added to bread creating potato farls (flatbreads) and boxty, a potato-based pancakes. This was a way to stretch flour supplies during times of scarcity.

Lastly, griddle cakes, made with flour, buttermilk, baking soda, and sometimes eggs, were common in households without ovens, particularly at special occasions or on Sundays.

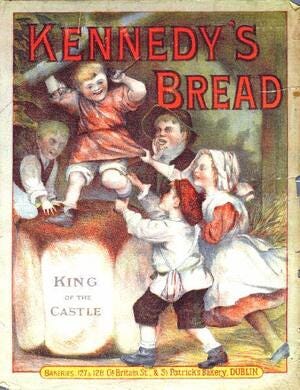

Over the course of the 19th century, urban bakeries opened in cities like Dublin, Cork, and Belfast, bakeries providing yeast-risen breads, biscuits, and cakes for the middle and upper classes. These bakeries produced wheaten loaves, fancy pastries, and even French-style breads. These bakeries not only supplied daily bread and confections but also played significant roles in the social and economic fabric of their communities.

Two such bakeries were Boland’s and Jacob’s, both located in Dublin. Boland's Bakery was Dublin's largest bakery in the late 19th century. The original bakery was located near Capel Street, between Mary (Abbey) Street and Little Mary Street. The company produced a range of products, including bread, biscuits, cakes, confectionery, and flour, with biscuits becoming a primary focus over time. The bakery's building on Grand Canal Street played a notable role during the 1916 Easter Rising, being occupied by Éamon de Valera and his forces.

Jacobs was established in 1851 by brothers William and Robert Jacob, this bakery began on Bridge Street in Waterford before relocating to Bishop Street in Dublin in 1852. Jacob's became renowned for its biscuits and expanded operations to Liverpool in 1914. The Dublin premises on Bishop Street were also among the buildings occupied during the 1916 Easter Rising.

Jacobs are most famous for their cream cracker. Jacobs remains at the forefront of Irish food consciousness in terms of this crisp pinhole biscuit. For many Irish people, freshly buttered Jacob’s cream crackers and a cup of tea was tantamount to a meal.

Other bakeries around the country, such as Barney Hughes' Bakeries in Belfast and McCann's Bakery in Newry also contributed to the popularity of affordable bread and other confectioners. The ‘Belfast Bap’, a small pan loaf (150–200g), originated in the 1850s from baker Barney Hughes, who created the bread to feed the poor of Belfast during the Great Famine.

It is during the 19th century that many bread and cakes we associate with traditional Irish emerge. These bread and cakes, such as soda bread, are often connected to Ireland in some quasi-timeless manner. However, they all have concrete contexts in terms of their time and place in 19th century Irish baking. From Barmbrack to scones and spiced cakes to porter cake, our image of traditional Irish baking is firmly rooted in the 19th century.

By the late 1800s, Irish baking began incorporating imported spices (like cinnamon, nutmeg) and dried fruit at a national level. Rich fruit cakes became a feature of Christmas and weddings.

Throughout this period, British colonial policies prioritized wheat for export, so traditional Irish baking relied on cheaper grains like oats and barley. However, as we have seen, urban bakeries and wealthier households adopted more British baking styles, including sponges and Victoria-style cakes. Tea culture, which became widespread after the Famine, led to an increase in home baking of scones, soda bread, and fruit cakes to accompany tea.

Excessive tea-drinking in the late 19th century promoted a new ‘moral panic’ regarding the Irish diet. Many saw tea as a stimulant with no nutritional value, only to be used for ‘purposes of exhilaration and hedonism’ (Miller 2015: 324). By 1904, many considered tea-drinking to be out of control, sending some to the asylum (Clarkson and Crawford 2001). Though it’s hard to understand this now, the debate at the time was a serious one, with many people abstaining for fear of becoming a ‘tea drunkard’.

After the Great Famine, dietary changes influenced baking. There was more reliance on bread than potatoes, especially in urban areas. There was also an increase in tea and sugar consumption, leading to more frequent sweet baking. Lastly, there was a decline in oat-based baking, replaced by wheat-based soda bread and brown bread. This shift would regulate oats to porridge in the 20th century with less and less households making oat-based bread. However, oat biscuits remained popular as well as flapjacks (something my mother would frequently make).

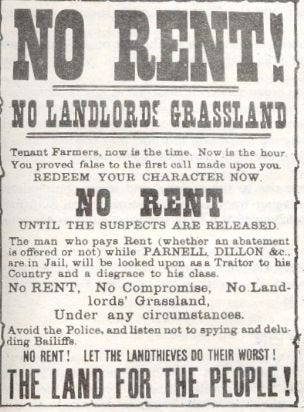

It must be said that during the famine, more food was exported out of Ireland than before or after the famine. Globally, Ireland was known for its beef, grain, and dairy. However much of this was shipped to Britain and elsewhere, often at the expense of local food security. Irish tenant farmers worked small plots, often growing crops for landlords rather than their own subsistence. This led to food shortages and poverty which fueled resentment against British rule.

While we don’t often reflect on how food shaped the concerns of Irish nationalists, the Land Wars (1870 onwards) pushed for peasant land ownership, improving food security for some. Thus, our nascent food culture emerges at the same time as the revival of many other cultural interests.

The Irish Independence movement saw a push for economic self-sufficiency, which included discussions about Irish agricultural policy. While the words ‘food culture’ may have been far from their lips, these farmers advocating for land reform were slowly changing the ways in which food was produced (and for whom) in Ireland.

Ultimately, baking in Ireland between 1801 and 1922 is a tale of two Irelands, one rooted in hearth traditions, using simple, readily available ingredients like oats, barley, soft wheat, buttermilk, and potatoes, the other a manner of well-equipped kitchens, continental influences and extensive baking producing fine breads, biscuits, cakes, and puddings.

However, the introduction of baking soda revolutionized Irish bread-making, leading to the enduring legacy of soda bread in the domestic space. In contrast, urban bakeries, such as Kennedy’s who operated from the 1850s onwards, brought yeast-risen breads to the masses, especially in Dublin.

Despite economic hardships, Irish baking culture remained rich in tradition, adapting to social and political changes over time during the period. Many of the breads and cakes produced between 1801 and 1922 are now iconically Irish. The two Irelands, which existed through the 19th century would merge in a new independent Ireland after 1922. Though we would still struggle to assert our own food identity, in baking, as well as other forms of food culture.

It’s well past time we dropped the term ‘The Great Famine’, even our current president who should know better is guilty of using that term.It was never a famine in the true meaning of that word. It was a genocide of a million Irish citizens for which the English have never accepted responsibility.

https://irishmemorial.org/learn/the-great-hunger/

Love this! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining industry line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes (mostly NYC and L.A.) for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com