Each time I go down the rabbit hole of research on Irish food, I find far more than I expect. Hence this week, we’re just going to look at the Brehon laws (Ireland’s native legal system and one of the oldest in Europe). Of course, the Brehon laws span Iron age Ireland up to the 17th century and represent the voice (so to speak) of the Gaelic order of Ireland. Of course, the early church, which introduced writing to Ireland, modified these laws, in the transition from a pagan to a Christian Ireland, but in all, we can get a good look at the Irish baking tradition by examining these laws.

As we have seen, up to the turn of the new millennia in Ireland, bread and baking had changed little in its first 8,000 years on the Island. Though sourdough loaves may have been made (the technology to bake them existed in the Greek and Roman Empire and trade and migration may have brought these techniques to Ireland, especially to the higher classes), bread remained very much at the level of flatbreads and oatcakes, flavoured with wild herbs, nuts and honey.

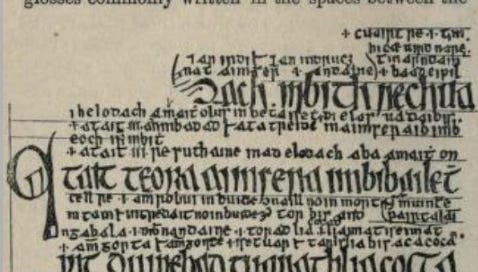

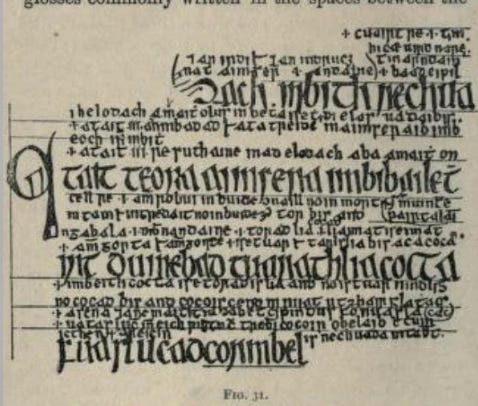

This changes with the arrival of a coherent Gaelic culture under the Brehon laws, especially once they are written down. The Brehon laws were, as I said, the native legal system of Ireland. Though they became codified in the early medieval period (with the advent of writing in Ireland), they are said to go back at least to the Iron age in terms of an oral transmission which was passed on from generation to generation.

While I don’t want to get bogged down in a detailed analysis of these laws (there are a multitude of books on the subject, such as Jo Kerrigan’s Brehon Laws: The Ancient Wisdom of Ireland (O’Brien Press, 2020), I do want to look at what they say about hospitality, food, and of course, the baking of bread. The Brehon Laws contain many references to food, covering everything from hospitality obligations to agricultural production and even penalties for food-related offenses, such as poisoning. Food was a fundamental part of social status, legal obligations, and community structure in early Irish society. We would do well to remember this in age that seems to devalue food culture at every turn.

The Brehon Laws show how food was deeply integrated into law, culture, and economy in ancient Ireland. It wasn’t just about sustenance (as it often is nowadays); it was a symbol of status, hospitality, and social duty. That is to say, it was of cultural importance as well as economic consequence. You were what you ate.

According to the laws, hospitality was a legal and social duty, particularly for people of higher status, such as kings, chieftains, and bó-aire (wealthy landowners). A host was obliged to provide food, drink, and shelter to travelers or guests, especially poets, judges, and other respected figures. Failure to provide proper hospitality could result in legal penalties (these penalties were civic as opposed to criminal).

The amount and type of food a person was entitled to depended on their status in society (airecht). High-status individuals could receive elaborate meals, often including meat, dairy, and ale, while lower-status individuals had simpler fare like porridge, gruel, and bread. There were laws outlining the portion sizes and specific foods to be served to different classes.

The Brehon laws also commented on food production, especially agriculture. There were strict rules about grazing rights, crop protection, and land use. Certain animals and crops were protected by law, with fines for their destruction. Milk production was highly regulated, with specific fines for harming a milking cow.

Wild food stuffs were also covered, with certain trees, such as apple trees and hazelnut bushes, were legally protected. Cutting down a fruit-bearing tree without permission resulted in heavy fines. Hunting laws regulated who could take wild game and under what circumstances. Cuts of a recently downed deer had to be divided according to social rank, not who was the hungriest.

The Brehon laws stress the importance of absolute of dairy and meat. As dairy products (milk, butter, curds, and cheese) were staples of the Irish diet, they held high economic value in relation to the laws. Cattle were considered a measure of wealth, and disputes over cattle ownership were common. Beef, pork, and fish were common protein sources, but the type of meat a person could eat often depended on their social status. Bread was ranked below beef and dairy.

Two other aspects of the Brehon laws regarding food and drink are revealing in relation to the kind of food culture that existed in Ireland at the time. The production of beer (and its consumption) was tightly control. As now, beer/ale (beoir) was a common drink, and brewers had specific legal responsibilities in relation to its production. If a brewer sold bad beer, they could be fined or even temporarily banned from brewing (I’m not sure this happens anymore.) On the side of the drinker, excessive drunkenness, especially leading to disorderly behavior, could result in penalties and fines (as today). Of course, the higher standing one had, the less lightly these fines would affect you. For those interested in beer in ancient Ireland, check out the new book by Dr. Christiana Wade, entitled Filthy Queens (Nine Nean Rows, 2025).

Food and drink also had a ceremonial and ritualistic significance for early Gaelic culture. Food played a role in key festivals in the Celtic calendar, especially around Imbolc, Bealtaine, Lughnasadh, and Samhain. Feasting was an important part of political and legal gatherings, and this was expressed through ritual. Oats, barley, and honey were commonly used in ceremonial meals, from gruels, porridges, to savoury and sweet breads. In much the same way that we celebrate significant calendar events with certain food in Ireland today, so did our ancient ancestors.

The Brehon Laws contain multiple references to bread, reflecting its importance in early Irish/Gaelic society. It was tied to social rank, legal obligations, and economic transactions. Bread was a staple food, and its production, distribution, and quality were all regulated by law. As bread was a primary food source, it was of particular importance for the lower classes, who have less access to meat and dairy. As in the preceding periods of Irish history, it was made from oats, barley, or wheat, however, who consumed which bread now depending on availability and social status.

Hence, bread was rationed and distributed according to social rank, with higher-status individuals receiving finer quality bread. This social stratification of bread was to remain in place for another thousand years, as the Anglo-Normans adopted this practice as well, preferring wheaten bread, sweeten with honey and spices for those ‘barons and wealthy merchants’ (Mahon, 1991: 71).

As I have already observed, under Brehon hospitality laws a host was required to provide guests with food, which included bread. The type of bread offered depended on the guest's social status. A noble might receive fine wheat bread, while commoners were given oat or barley bread. Failure to provide proper food and bread to a guest, especially one of high status, could result in legal fines as well as a loss of social standing.

Bakers were also kept in check through these laws. With a constant eye on quality, bakers selling inferior could lead to fines or compensation to the buyer. Some laws even specified the correct weight and size of bread to prevent bakers from cheating customers out of their daily bread.

Bread, as butter, could be used for payments or fines rather than money or cattle. In disputes over food supply, bread was sometimes used as a measure of compensation. Bread was always used in festivals and ceremonies, often being baked in special ways for seasonal celebrations like Samhain. Indeed, this use of bread as an offering was also adapted by the Irish Christian traditions (which already had its own tradition of the symbolic value of bread.

I’d now like to turn to the kinds of breads that are mentioned in the Brehon laws, which not only reflect the different grains available in Ireland but also the social status of the people consuming them. By the early medieval period (400–795 CE) bread was a staple food in early Ireland, and its type, quality, and availability were all legally controlled.

Breads Mentioned in the Brehon Laws

Arán (Wheat Bread)

Considered the highest quality bread, typically reserved for the nobility and higher-status individuals.

Made from wheat flour, which was more expensive and less common than oats or barley.

Served at feasts, legal gatherings, and as part of the hospitality laws.

Bairgen (Loaf Bread)

A general term for a loaf of bread, mentioned in legal compensation and fines.

Could be made from various grains, including wheat, barley, or oats.

Used in hospitality laws, where certain guests were entitled to specific quantities.

Bricten (Rough Barley Bread)

A lower-status bread, made from barley, which was grown more than wheat.

Coarser and less refined than wheat bread.

Common among the working class, farmers, and poorer individuals.

Daidbairgen (Poor Man’s Bread)

Made from oats or mixed grains, often of lower quality.

This type of bread was associated with commoners and those of lower social rank.

Used as a form of basic sustenance.

Losat (Ash-Baked Bread)

Bread that was baked in ashes rather than in an oven.

A simple, rustic bread that might have been used in fieldwork or travel.

Possibly an early form of flatbread or bannock.

Cáechbairgen (Blind Bread)

A term that could refer to unleavened bread or bread made without fine flour.

Might have been dense and heavy, with fewer ingredients.

Torthán (Small Round Cake or Bun)

Mentioned in texts as a small, sweetened (with honey) or enriched bread.

Used for ceremonial or special occasions.

All these breads would have been served with fresh butter, soft cheese (curd), or honey and would have been accompanied by ale or mead at feasts. Breads were served alongside stews and roasted meats in noble households or as a starter or prelude to the main meal (Mahon, 1991).

As with older breads, it’s difficult to ascertain what leavening agent was used, if any at all. Of course, a natural leavening agent of wild yeast and bacteria from the environment surrounding naturally leavened bread. A sourdough starter (used in both Greece and Rome) could have been used to help raise bread. This starter would capture natural yeasts from the air, creating a slow rise and a tangy flavour. Sourdough was likely used in wheat breads (arán), providing both rise and flavor.

Another option for helping bread rise would have been to use buttermilk or sour milk, common in early Irish diets, which would react with wood ash or ground seashells (containing natural alkaline substances) to create a mild leavening effect. This combination acts similarly to modern baking soda and buttermilk, producing carbon dioxide and causing the dough to rise. This method was likely used for oat and barley breads (bricten, daidbairgen).

Lastly, residual yeast from beer or ale brewing could have been used to leaven bread. Brewing was common in Gaelic Ireland, and the foam (barm) from fermenting ale could be mixed into dough to produce a lighter, airier loaf. This was a typical method up to the 19th century in Ireland, and many recipes of the 17th and 18th century specify the use of barm as a leavening agent.

The Brehon Laws shows us that bread was more than just food in Gaelic Ireland. It was a symbol of status, law, and hospitality. Distinct types of bread reflected rank, wealth, and legal obligations as well as being made especially for certain events or festivals. The early Christian church integrated this ideology into its own outlook of the world.

Next week, we will turn to the monasteries of early medieval Ireland (400-795 CE) as well as looking at how the Vikings (795-1169 CE) brought with them traditions from Scandinavia.

I hope you’re enjoying this little snapshot of Irish food history and that it is contributing to your understanding of the long history of food on the island of Ireland.

There is much more to Irish food than you think.

Until next week,

Jp.

I’m amazed at how much there is to say about Irish bread, Jp. And how it was embedded into Brehon Law. Enjoying the read.

Is é an t-arán crann seasta na beatha! Old Irish proverb, Bread is the staff of life! Your article certainly shows how important bread was in ancient Ireland.

The Scottish celts were equally fond of their bread. One of their sayings runs: Cha bhòrd gun aran ach ‘s bòrd aran leis fhèin. (’A table without bread is not a table, but bread is a table on its own.’) Very similar to Irish Gaelic.

Great wisdom in the old proverbs.