The food culture of Maynooth in Co. Kildare evolved significantly from the medieval period (c.1200) through the late 18th century. This was a feudal town dominated by the FitzGerald family, the Earls of Kildare (later Dukes of Leinster), whose seat at Maynooth Castle (and later Carton House) shaped local agriculture, economy, and diet. Over these centuries, social class influenced diet, from the lavish banquets of nobility to the humble fare of tenant farmers. Religious practices (Catholic fasting days, etc.), agricultural production, and periodic crises like famine all left their mark on what people ate in the town.

Maynooth’s food culture was strongly influenced by three key institutions tied to the FitzGerald legacy: Maynooth Castle, Carton House, and St. Patrick’s College. Each of these sites served as a center of hospitality, production, or provisioning that shaped local food practices including diets across social classes, agricultural supply, food customs, and the development of markets and trade. In this part, I shall look at how the castle played into medieval life in Maynooth.

The aristocratic FitzGerald family in Maynooth enjoyed a high-status diet reflective of their wealth and feudal power. Meats and game were central at their table: excavations at Maynooth Castle show abundant remains of prime cuts of beef and especially pork, with pig bones far more prevalent than on earlier sites. The nobles hunted deer (both red and fallow deer) for venison and exploited wild boar and seal. As I have mentioned in earlier episdoes, a seal’s bones found at the castle suggest the animal was taken both for its tender meat and valuable white fur. This variety of meat, including game and oysters and other seafood, indicates a “splendid diet enjoyed by the castle’s owners” (Hayden, 1996).

From its construction circa 1203, Maynooth Castle was the principal stronghold of the FitzGeralds. As the home of the Earls of Kildare, the castle not only hosted the noble family but also a large retinue of officials, soldiers, servants, and guests. The castle’s influence on food culture was multifaceted and its influence spread beyond its walls.

The castle contained great kitchens and buttery stores to feed the lord’s household. Historical records of other Anglo-Norman castles suggest daily butcherings and bread baking on a large scale. At Maynooth Castle, the high-quality diet evidenced by archaeology indicates that the castle kitchens prepared lavish meals. Large hearths and ovens would have produced huge quantities of trenchers (bread used as plates), roasted meats on spits, pies, stews in cauldrons, and baked treats for feasts. The existence of a castle brew-house or bakehouse is likely (nearby grain mills supported bread and ale production. The castle thus acted as a hub of culinary activity, employing bakers, brewers, butchers, and cooks, which in turn diffused skills and recipes to the town. For example, castle cooks might be experts at spicing and preserving food; these techniques could trickle down to local tavernkeepers or farmers employed at the castle.

Maynooth Castle was renowned for hosting notable guests, from Gaelic chieftains to English officials, and hospitality was a key part of noble culture. The Earls of Kildare were said to keep an open house for their allies, meaning frequent banquets. This required storing copious quantities of food and drink. The castle had extensive larders and wine cellars, and its own deer park or hunting preserve to supply game. When Silken Thomas (Lord Thomas FitzGerald) rebelled in 1534, it’s recorded he gathered allies at Maynooth, accompanied by nights of feasting before the siege. Feasts at the castle on saints’ days or family occasions (weddings, investitures) would spread food wealth into the community as well. Lesser guests and servants all partook, and local producers gained by supplying these events. The tradition of great feasts also set a social example: tenants might emulate their lord’s celebrations on a smaller scale during festivals.

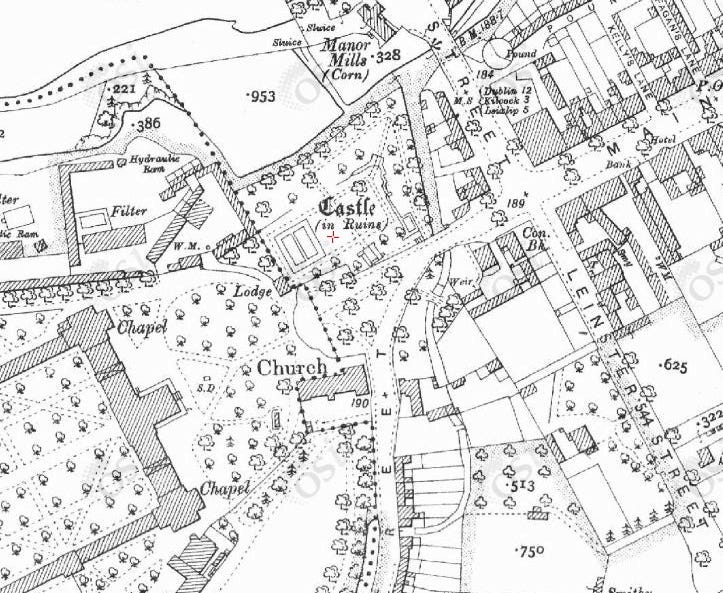

The castle’s needs shaped local agriculture. To provision the castle, surrounding lands (the demesne and tenant farms) had quotas to fulfill, from grain, livestock, fish, and firewood. Maynooth had at least one mill by the 14th century for grinding grain, undoubtedly processing oats and wheat for the castle stores. Peasants rendered cereal tithes and food rents (butter, pigs, and hens) which went into feeding the castle household. So, the presence of the castle stimulated production of certain foods: dairy products for the castle kitchens (the FitzGeralds were noted butter exporters at times), and market gardening for herbs and vegetables used in the castle’s more elaborate cuisine.

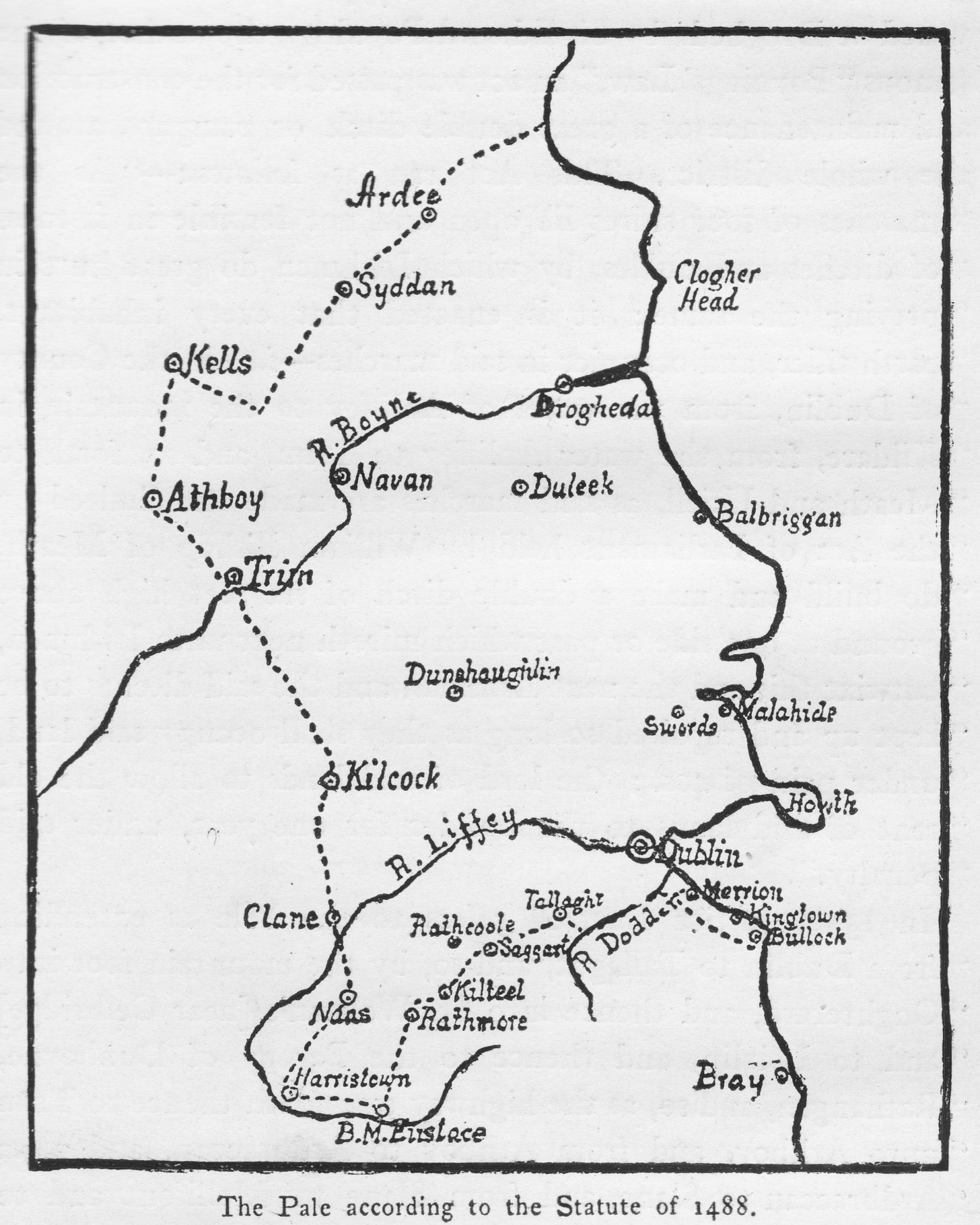

The castle also facilitated importing foods via the Pale: luxury items like figs, almonds, or wine could be brought from Dublin to Maynooth Castle for the lords, something ordinary folk would never see.

However, the castle’s direct influence waned after the turbulent 16th–17th centuries. It was heavily damaged in 1535 during Silken Thomas’s rebellion, and again in the 1640s wars, after which it was subsequently abandoned.

For a century (1535–1630) the FitzGeralds did not reside there, and even after a brief restoration in the 1630s by Richard Boyle (the Earl of Cork, who married into the family), the renewed castle fell in 1646 and was left a ruin. During this time, the locus of food influence shifted away (the earls lived elsewhere or in England), and Maynooth town’s economy suffered. Yet the memory of the castle’s grandeur persisted in the minds of the people of Maynooth. Even as a ruin, it provided fertile ground, its abandoned gardens and orchards continued to be used by townsfolk.

In all, Maynooth Castle’s role in food culture was as a medieval nexus of feudal food production and consumption, training local cooks and craftsmen, dictating agricultural output, and exemplifying both the abundance and volatility of high-status foodways in that era.

Due to the presence of the castle, Maynooth was granted a royal market charter in 1286 by King Edward I, allowing a weekly market on Fridays and an annual three-day fair in September. This indicates that by the late 13th century, Maynooth had grown into a significant local centre where produce could be exchanged. The weekly Friday market took place along Main Street or a designated market square (later maps show a market space off Straffan Road). Farmers from the hinterland would bring grains, eggs, butter, cheeses, livestock (chickens, pigs, calves) and garden produce to sell.

In turn, townspeople and the castle bought their provisions there. Regulations would have been set (often by the lord of the manor) to ensure standard weights and measures and collect tolls. For example, a customary practice saw the lord’s agent take a small cut of each sack of grain sold (the métage). Markets also facilitated inter-town trade. Maynooth would receive fish from the coast, or salt from overseas, in exchange for its surplus grain or wool.

The annual fair was a bigger event, drawing merchants from farther away. Historical atlases note the fair in Maynooth was held around the feast of the Nativity of Mary (early September) and was a venue for trading cattle and horses especially. At such fairs, specialty food vendors and even importers might appear (e.g. selling wine from Spain, spices, or dried fruit). Fairs also stimulated local cottage industries: ahead of the fair, farmers’ wives would churn extra butter, brew extra ale, fatten a pig, or bake oaten cakes to sell to fair goers. The fair thus injected cash into the rural economy and provided people an opportunity to taste or buy foods not regularly available (like a different region’s cheese or a barrel of pickled herring from a Dublin fishmonger).

Food in Maynooth was not merely sustenance; it was embedded in customs, religious observances, and historical events. It had its own culture. From daily rituals to annual festivals, and from enforced fasting to emergency famine measures, the cultural context of eating was significant in this period.

The types and availability of food in Maynooth between 1200 and 1700s were fundamentally tied to agricultural production in the region. Maynooth sat on fertile land in the Liffey valley and, as part of the Anglo-Norman Pale, benefited from relatively advanced medieval farming techniques. Over the centuries, there were shifts in what crops were grown, what livestock were raised, and how people procured wild foods.

Grains were the backbone of the diet and economy. Medieval sources and archaeology indicate that oats were the most common cereal among the populace, with barley next, while wheat and rye were grown in smaller quantities (see my earlier History of Baking). On the FitzGeralds’ demesne lands around Maynooth, wheat and rye were cultivated to supply fine flour for the lords. Barley was often kilned, partly for making malt (for brewing ale) and to make it shelf stable.

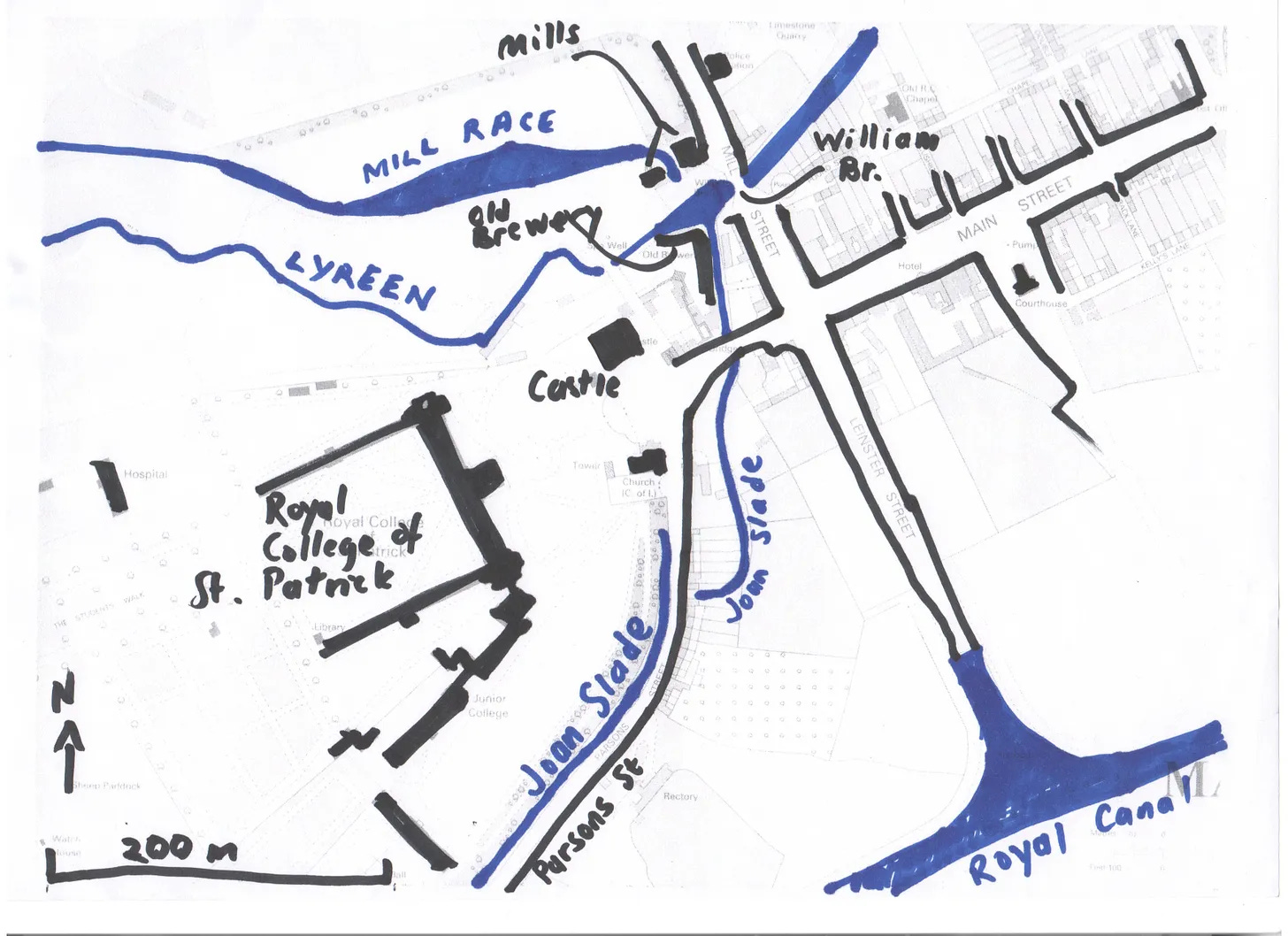

By the 13th–14th centuries, Maynooth had at least two watermills on the Lyreen/Rye streams for grinding grain, pointing to substantial arable farming. The primary breadstuffs were oat and barley for the poor (as oatmeal porridge or maslin bread) and rye or wheat bread for the rich. Notably, rye appears to have been a significant crop in the area – the castle hearth samples from the 1200s had a majority of rye grains.

Rye can grow on poorer soils and was valued for bread (it ranked just below wheat in prestige). Wheat, being finicky with Ireland’s damp climate, was grown on limited acreage; often the FitzGerald estate might import some wheat or flour from eastern counties or England.

Harvest season (late summer) was a critical time: all hands turned out to reap the fields. Harvest yields varied with weather. Good years meant plentiful bread and beer, whereas bad years spelled hunger (and indeed, multiple grain harvest failures triggered famine, as in 1740.

Herds and flocks were omnipresent in Maynooth’s rural economy. Cattle were highly prized – in Gaelic tradition a family’s wealth was measured in cows. In the 1200s, a typical tenant might have a cow or two for milk and a few pigs. The Anglo-Norman lords also raised cattle, but tended to slaughter more of them for beef than the Gaelic Irish did.

Archaeozoological analysis at Maynooth Castle shows cattle remains with an older age profile, meaning many cattle were kept to maturity (for dairy or as work oxen) and only later butchered. This suggests a mixed approach: the castle needed fresh beef, but cattle were too valuable to kill young. Pigs, on the other hand, were a fast-reproducing source of meat and were heavily utilized: the castle bone assemblage had more pig bones than even sheep or cattle.

Pigs were raised by both villagers (who let them forage in woods for acorns) and by the estate in controlled numbers. Pork was often salted or smoked to preserve it; the castle findings even hint that the prime cuts of pig might have been cured and consumed off-site or later. Sheep played a minor role in Maynooth. Sheep were kept more for wool than meat. Still, mutton would be eaten occasionally, and lamb at Easter was a treat. By the 18th century, estate records from Kildare show improved breeds: the Duke’s estate had large Shorthorn cattle and sheep breeds introduced, which yielded more milk and meat, benefiting the diet of those who could afford them.

Dairy products from cattle were enormous in quantity. Each small farm churned butter, much of which went as rent to the landlord’s storehouses. Kildare was known for good butter. Some was sold at markets (Ireland exported butter in firkins abroad in the 18th. often through merchants in nearby Dublin). The local diet was enriched by the “stunning variety of milk-based foods” from basic whole milk and buttermilk to soft curds, cheeses, and sour fermented drinks. Meanwhile, every harvest season, after grain was in, came the slaughter of livestock that could not be fed over winter (especially pigs in November).

Martinmas (Nov 11th) was the traditional butchering time, a community event where neighbours helped each other process pigs into bacon and black puddings (blood sausage). This annual influx of meat was followed by the lean months of late winter when stored grain might run low and people relied on hardy crops like peas, beans, and brassicas to survive until spring milk and early greens.

Cultivated gardens were an important supplement to diets. Medieval Maynooth town plots had “toft and croft” layouts, a house with a garden behind. In these gardens, people grew cabbage, onions, garlic, leeks, beans, peas, and medicinal herbs. There is evidence that parsnips were among the root vegetables grown in pre-potato Ireland. The Normans loved orchards: apple trees are the primary fruit noted as cider was popular in the Middle Ages in Ireland.

An archaeological study nearby Maynooth noted that medieval inhabitants gathered wild apples and hazelnuts, suggesting a mix of cultivation and foraging. The FitzGeralds no doubt had orchards on their demesne. In 1460, there’s record of an “orchard of Maynooth” being tended (implying pears and apples).

Beyond farming, the landscape around Maynooth provided wild food resources that supplemented diets, especially for the higher classes (in the case of hunting) and the lower classes (foraging and fishing out of necessity). The FitzGeralds maintained deer parks, one is later documented at Carton, and earlier they had a private hunting wood for deer and wild boar (wild boar were extinct by 17th century, but domestic pigs gone feral or imported wild pigs might have been hunted. Fallow deer, introduced by Normans, were kept for hunting sport and meat.

The castle bone record confirms deer were “hunted and exploited for both raw materials and meat”. Noblemen and their retinues also hunted small game: hares, rabbits (introduced by Normans), game birds like partridge, woodcock, wild duck from the marshes, and pigeons. Commoners generally could not hunt deer (that was often forbidden as game law), but they did trap rabbits and birds, and catch fish.

The River Rye and nearby River Liffey offered freshwater fish: trout, salmon (seasonally running), eels, and pike. There was also likely a fish-pond tradition; monasteries commonly had carp ponds, but if any gentry in Maynooth did, it’s not recorded. Instead, fish were acquired via trade. As noted by Hayden, “marine fish were being exploited at the castle […] probably transported the fifteen miles inland from Dublin Bay up the River Liffey” (Hayden, 1996).

The castle and the town got sea fish (herring, cod, hake, flatfish) and shellfish like oysters and mussels from coastal fishermen. Oysters appear in the castle refuse, another high-status food. For the rural poor, foraging was crucial: they collected wild berries (blackberries, wild strawberries, sloes), nuts (hazelnuts), wild herbs (elderflowers), and fungi. In times of famine, people resorted to extremely rough foods – e.g. bog oats (seeds of wild grasses), shamrock and watercress, and even tree bark or nettle broth in the worst cases.

Fowling (catching wildfowl) in the Bog of Allen fringe or local wetlands provided extra protein in winter. Eels from the Rye were a delicacy for some and a fallback for others. A 14th-century source mentions eels from the River Liffey being plentiful. These natural food sources meant that even if crops failed, some nourishment could be sought in nature, though never enough to feed the whole populace for long, as is recorded in the famine of the 1740s.

Overall, Maynooth’s agricultural base in the Middle Ages was robust, especially under the guidance of estate management by the FitzGeralds. Yet, when climate or politics disrupted this system, food could become scarce, revealing its limits. There are several years when Maynooth flew foul to famine and war.

The Great European Famine of 1315–1317 was triggered by relentless severe weather and, in Ireland, exacerbated by the Bruce invasion (1315). While specific records from Maynooth are scant, we know the Pale region suffered failed harvests, and “many died of starvation”. As Maynooth was a seat of the Earl of Kildare (since 1316), the FitzGerald at the time (John FitzThomas) had to ration grain to his people. Grain stores would have been depleted, and cattle murrains (disease) in those years killed livestock, so milk dried up. Chroniclers say people ate “green herbs and water” by 1317.

The period around Silken Thomas’s Rebellion (1534–35) was disastrous locally. The siege of Maynooth in March 1535 led to the castle’s fall and “extensive damage”. Afterwards, English soldiers plundered the area. In 1541 a report noted many houses in Maynooth town were derelict, and fields lay untilled. This implies local famine or near-famine conditions in the later 1530s: many inhabitants fled or died. The FitzGerald estates were forfeited for a time, so there was no lord to organize relief. We can surmise that those who survived relied on gardening and foraging until the situation stabilized in the later 1500s when the family was reinstated.

The 1641 Catholic rebellion and subsequent Cromwellian conquest (1649–53) ravaged Ireland. Maynooth Castle, briefly refortified, was “badly damaged during the rebellion of the 1640s” and abandoned. Soldiers would have requisitioned food; the Civil Survey of 1654 captures a picture of the aftermath: two corn mills and two malt houses existed, but much land was confiscated and people displaced. Famine usually accompanies war, and indeed in the early 1650s famine and plague killed a huge portion of the Irish population. Kildare was heavily impacted by troop movements. We have no direct census of Maynooth’s losses, but a considerable number starved or died of disease when crops were destroyed. The town’s population and prosperity plummeted until restoration under the duke’s family in the 18th century.

In summary, Maynooth Castle’s role in food culture was as a medieval nexus of feudal food production and consumption, training local cooks and craftsmen, dictating agricultural output, and exemplifying both the abundance and volatility of high-status foodways in that era. The development of markets and trade in Maynooth provided the essential scaffolding that held the food culture together. It enabled exchange between town and country, rich and poor, local and distant.

From the chartered market of 1286, Maynooth’s ability to buy, sell, and transport food steadily improved, helping the community weather the feast-and-famine cycles of pre-modern Ireland.

Next week, we shall look at how Carton House, St. Patrick’s College and the construction of the canal (1796) helped laying the foundation for the more interconnected food system of the 19th and 20th century.

Best, Jp.

23rd June, 2025.