Gaelic food culture is not something we speak of regularly in Ireland. It exists, of course, but its legacy is obscured by eight hundred years of colonial rule. Moreover, our ‘Irish’ food culture is a blend of the many peoples that have inhabited the island of Ireland, not just the Gaels. Though we may aspire to locate our native heritage in a Gaelic and/or Celtic spirit, the reality is much more complicated.

The reason we locate much of our post-independent identity in the image of the Gaels is because they are the first ‘historical’ people on the island. By historical, I mean they are the first to document themselves using the written word. The Gaels were a Celtic people who spoke a language called Goídelc, hence their name.

But the Celts didn’t bring the written word to Ireland. That was developed a couple of hundred years later by Irish scholars in the 4th century AD, influenced by Latin script through contact with Roman Britain. While mythology attributes it to the god Ogma, it was most likely a script devised by the Irish elite or learned classes for marking names and territories. Ogham was also as a practical tool for demarcating status in the fragmented tribal society of early Christian Ireland. Its use flourished especially by many who may had traveled to or had contact with Roman Britain.

As we witnessed in the first part of our food history of Maynooth, excavations at the site of Maynooth Castle reveal that long before the stone Norman keep was built (c. 1180s), the site had an early medieval Gaelic farmstead. Archaeologists uncovered at least two small post-and-wattle round houses (about 5 m across) with central hearths, and evidence of cultivation furrows running across the site. These furrows show that crops were actively grown there until the Anglo-Normans arrived in the 1170s.

Maynooth was an agricultural settlement in the Early Christian period, even though no large monastery or town existed at that time. Nearby, an Early Christian burial ground was discovered on Maynooth’s outskirts (at Moneycooly), containing over 50 east–west oriented graves (typical of early medieval Christian burials). Associated excavation finds included a gully containing animal bones, a whetstone, and metalworking slag, evidence that the community engaged in everyday farming and craft activities alongside their mortuary practices.

While no ringfort was detected at that site, the scattered pits, bones, and tools suggest a domestic farming settlement in the Maynooth area during the Early Christian era.

Although Maynooth itself was not a major monastic centre, its hinterland had early ecclesiastical sites. For example, Taghadoe, just east of Maynooth, features a round tower and church ruins indicating an early medieval monastery.

Such sites would have had gardens and farm plots to support their communities. In Co. Kildare at large, the monastic city of Kildare (founded by St. Brigid in the 5th century) was famed for its dairy herds and hospitality. While direct archaeological data from Kildare monastery is limited, historical accounts by Cogitosus (7th century) praise St. Brigid’s community for feeding the poor and hungry, implying an abundant food supply of milk, meal, and meat in that region.

Small finds across Co. Kildare support this agrarian picture: for instance, a large early medieval enclosed farmstead at Killickaweeny (near Kilcock, where I went to secondary school) yielded thousands of butchered animal bones, remnants of houses and hearths, and a variety of tools. Notably, stake-holes around a central hearth at that site held cooking spits for roasting meat, and a rotary quern was found for processing grain. All these remains demonstrate a thriving food culture, crops grown and milled, livestock raised and slaughtered, and meals prepared over open fires, in the Maynooth/Kildare area during the Early Christian and Gaelic medieval period in Ireland.

Throughout the 400–1200 AD period, the people of Maynooth and broader Gaelic Ireland cultivated a variety of grains. Archaeobotanical studies of early medieval Irish sites show that hulled barley and oats were the dominant staple crops. Barley was versatile, used for both making bread and ale, while oats were vital for porridge and gruel.

Wheat (often the finer ‘naked’ wheat) was grown in smaller quantities; it was present at many sites but not the primary crop. Wheat was reserved for high-status households or special bread (See A History of Irish Baking: Part 4). Rye appears only rarely as a minor crop. There is evidence of legumes like peas and beans in early medieval Ireland, though only occasionally, grown in gardens or gathered as wild pulses. Flax was cultivated for fibre to make linen while its seeds were used in cooking (whole or preseed) as continues today in many Irish soda breads.

In the Maynooth area, the discovery of a rotary quern stone at Killickaweeny (located between Kilcock and Enfield) shows that grinding grain into flour or meal was part of daily life. The cultivation furrows found under Maynooth Castle similarly indicate plots of cereals were sown and harvested locally. By the later early medieval period (around 1000–1100 AD), there is evidence for a greater emphasis on tillage farming, more sites yield cereal remains and a wider variety of crops, suggesting that arable agriculture became increasingly important over time. This growing output of barley, oats and other crops would have supported a rising population as well as the food demands of monasteries and chieftains in Kildare.

Animal husbandry was at the heart of Gaelic food culture, and the archaeological bone evidence confirms a heavy reliance on domestic animals. The cattle were paramount, regarded as the ‘currency’ of early Ireland for its value in dairy and meat. Large cattle herds were kept around Maynooth. Even if not slaughtered frequently, cattle provided a steady supply of milk (to be made into butter and cheese) and could be butchered for beef on special occasions. Pig rearing was also extremely important for daily meat needs, pigs mature quickly and produce large litters, making pork a common protein. In excavations of early medieval farmsteads in Kildare, bones of cattle and pig usually dominate the assemblages of food waste.

Again at Killickaweeny over 9,000 fragments of animal bone were recovered, many showing cut-marks from butchery. The remains included plentiful cattle and pig bones, indicating that beef and pork were staple meats. Sheep and goats were also raised, though in smaller numbers; they provided mutton or goat meat, milk, and wool for clothing. Skeletal remains of sheep/goat are routinely found alongside cattle and pig in early medieval layers, confirming their role in the diet (mutton stew and lamb were likely occasional fare, and goat’s milk could be used like cow’s milk).

Poultry was another key component in the early medieval diet. Chickens were introduced to Ireland by trade with the Romans and were kept for eggs and meat. While chicken bones are less frequently reported in excavations, due to poorer bone preservation or lower quantities, early texts imply that eggs and poultry were known foods. For instance, monastic rules refer to eating eggs during Lent, and feasting traditions mention roasted fowl.

Not surprisingly in Gaelic Ireland, dairy was a dietary cornerstone. Cows (and to some extent sheep/goats) provided abundant milk, which was consumed fresh or processed into butter, curds, and cheese. Butter was a highly prized staple, so much so that it was used as a form of tribute and currency. The Brehon laws indicate that tenant farmers paid part of their rent to chieftains in butter and other foodstuffs.

Archaeologists have remarkable evidence for this in the form of bog butter. Dozens of wooden tubs or skins filled with butter were deliberately buried in peat bogs across Ireland. The cool, oxygen-poor bog could preserve butter for months or years, acting as a natural refrigerator.

In Co. Kildare, a 35-kg oak barrel of butter was found in a bog, an astonishing discovery dated to the Iron Age or early medieval period. One study catalogued 274 instances of bog butter from the Iron Age to medieval times, concluding that the practice was largely for preservation and safekeeping of valuable dairy produce. Though I am now fascinated with the aroma possibilities of this butter, preservation was the primary aim for burying this butter.

Of course, butter was a valuable commodity in Ireland during this period, and it could even be used to pay taxes and rents. The Brehon laws note that butter was acceptable as cáin (tribute tax) from farmer to lord. A later record from 1609 shows an Irish abbey exacting “yearly twenty-four methers of butter and fifty methers of barley” as food-rent, illustrating how important butter and grain were in the economy.

Apart from butter, people also consumed curds and soft cheese (usually the by-product of butter-making). Early literature makes frequent mention of curds (Irish gruth) and buttermilk – for instance, it was common to offer guests curds with bread and onions, or to mix curds with porridge. Hard cheeses could be made for longer storage, though the simplest farmhouse product was a soft, yogurt-like curd.

As with the Neolithic people who lived in Kildare/Maynooth, early medieval people in Kildare supplemented their diet with wild foods gathered from the surrounding landscape. Forests and wetlands around Maynooth would have been sources of game, fish, and edible plants.

Gaelic nobles and commoners alike engaged in hunting. The largest wild animal in early medieval Ireland was the red deer, and remains of red deer have been found on many sites, indicating venison was often on the menu.

At Maynooth Castle, deer bones were identified in the middens (including later-introduced fallow deer in Norman times). This suggests that venison was a prestige food, eaten at feasts or used to honour guests.

Other game would have included the wild boar in the early centuries (though true wild boar went extinct in Ireland by the Middle Ages, domesticated pigs took their place for pork). The hare was a common small game animal, hare bones turn up in some assemblages (even at Maynooth Castle), implying that hare stew or roast might spice up the diet on occasion.

Gaelic hunting dogs were highly valued for chasing hare and deer. Wild birds were also taken, species like duck, geese, woodcock, pigeons, and grouse could be trapped or shot with bows. For instance, fragments of bird bones are reported alongside animal bones in medieval deposits. Swans and cranes are mentioned in contemporary writings as fancy banquet fare for kings, though such feasts are more legend than everyday reality. More commonly, farmers might snare wild fowl or collect eggs of wild birds from nests.

Rivers and lakes in the Kildare region (the Rye Water, Liffey, and Bog of Allen wetlands) provided freshwater fish and other foods. As we know, early Irish diets included fish: salmon and eel were especially esteemed. The River Liffey and its tributaries were known for salmon runs. Eels were plentiful in marshes and could be caught using basket traps or tridents; eel was a staple, often eaten smoked or dried. They were also used as currency to pay rent.

While fish bones are less frequently preserved, the excavation of Maynooth Castle recovered numerous fish bones alongside animal bones, showing that by the high medieval period (1000AD+) a variety of fish such as river trout, salmon, and pike were being consumed by Maynooth locals.

Monastic rules required abstinence from meat on Fridays and during Lent, so fish and fasting foods had importance in Christian diet, one reason even inland sites procured fish. Moreover, the finding of seal bones at Maynooth is intriguing evidence that coastal resources made their way inland. These immature seal bones might indicate traded sea fish or seal oil from Ireland’s coast, or perhaps seasonal hunting of seals on eastern coasts with the meat transported to lordly households. Salted sea fish (herring, cod and mackerel) was imported inland as well. By the 12th century there was certainly some trade in salted herring making its way inland to Maynooth.

As with early settlers, people of Maynooth augmented their diet with wild fruits, nuts, and greens from the locale. The most ubiquitous foraged food was the hazelnut. Archaeologists often find charred hazelnut shells in early medieval cooking hearths, suggesting they were roasted or used in porridge. Hazel bushes grew in Kildare’s woodlands, providing an autumn glut of protein-rich nuts that could be stored.

Berries were seasonally gathered: blackberries, sloes (wild plums), elderberries, and bilberries would add variety and vitamins to the diet. Wild apples and crabapples could be collected or grafted onto cultivated stock over time. Although preservation of soft fruit remains is rare, medieval poetry and later folklore celebrate these wild flavours.

The poem Samhradh (Summer) appears in early medieval Irish texts and is part of a tradition of nature poetry that praises the abundance and sensory pleasures of the seasons. One version is found in the Saltair na Rann or in other early Irish monastic collections, and it includes lines that describe summer’s pleasures: birdsong, warmth, green fields, berries, and honey: symbols of seasonal bounty.

Summer-time, season supreme!

Splendid is colour then.

Blackbirds sing a full lay,

if there be a slender shaft of day.

...

Berries on hedges in tight clusters,

honey in wood and in field.

This tradition reflects how wild seasonal foods like fraochán (bilberries), blackberries, and honey were not just dietary necessities but also poetic motifs. These early seasonal poems, including those found in The Book of Ballymote or The Yellow Book of Lecan, capture the monastic and rural appreciation for nature’s rhythms, particularly in early medieval Ireland, where the observation of natural abundance had spiritual and cultural resonance.

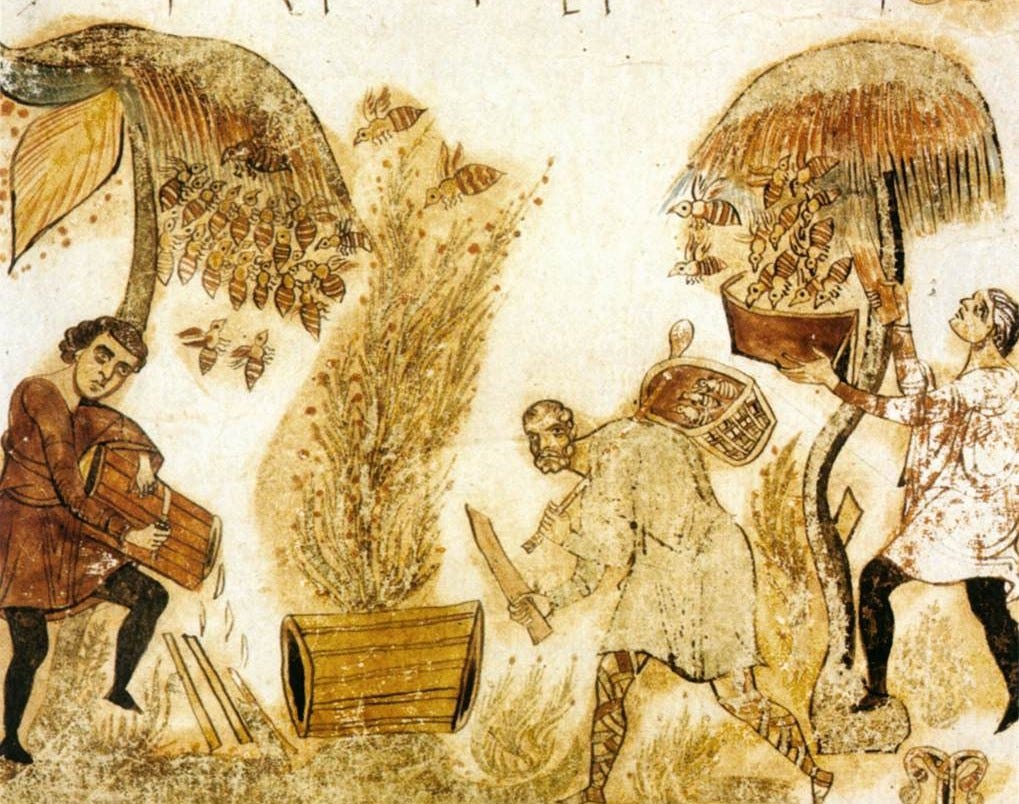

Speaking of which, honey was an important wild-sourced food: beekeeping was practiced (bees were kept in skeps or bee-boles at monasteries and farms), and wild bee colonies in tree hollows were also raided for honey and beeswax. Honey was the chief sweetener for foods and drinks and fermented into mead (a type of honey wine) for special occasions. The presence of bees is noted in Brehon law, which carefully regulated beekeeping and the sharing of swarms, emphasizing how valuable honey was to Gaelic diet and hospitality.

Early Christian and medieval Gaelic cooking was centered on the open hearth. In the small round houses excavated near Maynooth, fire-pits or hearths were found, some with evidence of stakes or post-holes around them. Archaeologists interpret these as supports for spits or hangers to roast meat over the flame. Meat (such as joints of pork or beef) could be roasted on a spit or grilled over embers. However, the most common cooking method was likely boiling or stewing in cauldrons. The Irish possessed large metal cauldrons (often bronze or iron). Many Irish legends frequently reference heroes feasting from great cauldrons.

Archaeologically, iron cauldron fragments have been found in some crannog (lake dwelling) sites, indicating their use. Into these cauldrons would go cuts of meat along with water, herbs, and vegetables to make hearty stews. A broth of beef or bacon with barley and greens was a staple dish for many. Baking was also known, though without ovens in ordinary homes, baking was done on the hearth or in simple clay-domed ovens.

Unleavened flatbreads or oatcakes could be cooked on hot flagstones or iron griddles set by the fire. The richer households and monasteries, which grew wheat, could bake leavened bread from wheat flour – likely as small hearth loaves or bannocks. There is evidence that cereal porridges and pottages were a daily fare: oats or barley boiled into a thick porridge, eaten plain or with milk. The Irish term lían referred to a kind of gruel often flavored with butter or buttermilk. Even in high-status feasts, a common dish was a pottage of grains and vegetables served alongside roasted meats. To flavour their food, early medieval cooks used what was on hand, salt (if available), herbs like wild garlic, watercress, parsley, and onions or leeks (the latter were grown in monastery gardens by the 8th–9th century).

Given the seasonal cycle of abundance and scarcity, Gaelic communities developed ways to preserve food for winter and lean times. One key method was dairy preservation, turning perishable milk into long-lasting products. As I mentioned above, butter could be preserved by burying it in cool bogs or storage pits; even without bogs, crocks of butter were kept in cold, damp cellars or souterrains (underground chambers often found in ringforts, which served as storage cellars).

Cheese-making was another form of preservation: by removing moisture and adding salt, cheese could keep for months. Meat was usually consumed fresh after slaughter (especially beef, which might be finished in late autumn culls), but excess could be salted or smoked. Early Irish texts occasionally mention salted pork, likely bacon sides or hams were dry-salted and hung in the rafters above the smoke of the hearth to cure. The prevalence of pigs (which could be slaughtered year-round) meant pork could be cured into bacon to last through winter.

Fish were often eaten fresh, but salmon or eels might be split and air-dried or smoked as well (a practice later well-documented in medieval Ireland). The use of salt in early medieval Ireland was limited by its cost, coastal salt pans produced some, and mineral salt deposits were known, but salt was precious. Nonetheless, Irish preservation didn’t rely solely on salt: drying and fermentation played roles.

Grain was dried in small kilns to prevent spoilage (archaeologists have found remains of stone-built corn-drying kilns from this period, used to dry harvested oats/barley over a low fire). Dry grain could then be stored in sacks or bins safely. The discovery of large storage pits at some ringforts suggests that cereals were sometimes stored underground in sealed pits, perhaps creating a silo effect to keep out rodents and moisture. For example, the Killickaweeny enclosure had several lined pits and a big water-filled pit that may have doubled as a cistern and a food-processing area.

Without widespread pottery use (Gaelic Ireland had little coarse pottery, the potter’s wheel and glazed ceramics came with the Normans), people relied on organic containers for storage. Food and liquids were kept in wooden barrels, tubs, leather bags, and baskets. The bog butter finds illustrate the variety: butter was found stored in wooden kegs, carved troughs, skins, even in a carved wooden mether (drinking cup) in one case. These were everyday container types on farms. In normal use, a churn (often a tall butter churn) would serve to both churn and then store butter; surplus could be repacked into a keg and buried or kept in a cool shed.

Meat and grains might be stored in large wooden chests or hung in bags from rafters (to keep from damp and pests). The absence of ceramic jars meant souterrains (the underground tunnels often built under ringforts) were especially useful – acting like root cellars to keep dairy, ale, or even root vegetables cool.

Indeed, the cool constant temperature of a souterrain would help butter and milk last longer in summer. Brewing and beverage storage also relied on wood: ale was brewed in tubs and stored in barrels.

Historical and literary sources from the Early Christian and Gaelic medieval period provide additional colour to the archaeological evidence of Maynooth and its surrounding area. Early Irish law texts and annals frequently reference food: both as daily sustenance and as social currency of culture.

The Brehon laws, as observed, detail obligations of hospitality (díguestais), indicating what different ranks should be served when traveling. From these we learn that a lord was expected to offer generously “a fattened cow, fine wheaten bread, and good ale” to important guests, whereas a poorer farmer might offer barley bread, butter, and curds to a visitor.

Such distinctions underline the staple foods available and their relative value. The law tracts also confirm that many food items doubled as forms of tribute or payment. The Annals (monastic chronicles) occasionally mention feasts and famines, giving a sense of diet. In famine years, they record people resorting to eating wild plants, a stark reminder that the normal diet was heavily dependent on successful harvests and dairy yields.

The 8th-century saga Scéla Muicce Meic Dathó (“The Tale of Mac Dathó’s Pig”) centres around a legendary feast in Leinster where a giant boar is roasted to divide among heroes, highlighting the high esteem for pork at banquets. Similarly, the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge (“Cattle Raid of Cooley”) is essentially about stealing a prize bull – reflecting how cattle were viewed as literal treasures of nourishment and status.

The Life of St. Brigid (by Cogitosus, c. 650 AD) contains miracles that revolve around food: in one story, Brigid miraculously replenished the stores of butter she had given away, and in another, she turned water into ale to sustain visiting clerics. These tales, though hagiographic, point to butter and ale as everyday essentials in 6th-century Kildare, and by extension, Maynooth.

Beer (ale) was indeed a common drink brewed from barley; every noble household had a brewer. Another early text, the Rule of St. Columbanus (c. 600 AD), while meant for continental monasteries, sheds light on diet: Columbanus allowed his monks a scant daily ration of bread, beans or vegetables, and water – meat was reserved for the sick. This ascetic diet shows the contrast between monastic ideals and secular plenty. In secular life, feasting customs were very important: the brehon laws mention a cauldron of hospitality that should always be on the fire in a chieftain’s hall, and the tradition of the óircheas (guest’s portion) and curadmír (champion’s portion) in tales demonstrates the ritual of meat distribution at feasts. Guests were seated according to rank and served multiple courses: perhaps a first course of cold dishes (like curds, cheese, bread), then a main course of hot stew or roasted meat, and plenty of ale or mead to drink.

Even foreign observers commented on Irish foodways. In the 12th century, the Norman chronicler Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) wrote that the Irish “live on beast’s flesh and milk” more than on bread, a somewhat biased observation, but not entirely untrue for the pastoral economy of the time. He noted the Irish drank milk and whey and had butter in great quantities, reflecting a diet rich in dairy. Gerald was disparaging about their eating habits (claiming they ate too much lightly cooked or even raw meat), but his account still confirms the centrality of cattle products and meat in Gaelic nutrition.

By 1200, Maynooth had become a Norman stronghold, but interestingly the food remains show both continuity and expansion of diet. The Norman lords of Maynooth kept a deer park (bones of fallow deer were found) and even continued to consume marine resources. This later evidence, though beyond the Gaelic era, hints at the broad spectrum of Norman foodways in Maynooth: farmed animals, hunted game, and traded fish. All reflected food practices that had roots in the preceding Gaelic period.

The evidence from Maynooth and its wider context in Co. Kildare reveals a vibrant food culture during the Early Christian and Gaelic medieval period. Both archaeology and literature paint a consistent picture of a society where food was not only a necessity but a centerpiece of culture and capital, binding communities through shared feasts, sanctifying hospitality to guests, and even serving as an index of status and piety. From the humble farmer’s table in early Maynooth to the high king’s banquet, the Gaelic Irish managed a diverse diet from the resources of their land, leaving behind tangible traces in charred grains, animal bones, and utensils: all echoing the diverse foodways of Maynooth from the 5th to the 13th century.

In part three, we’ll look at food culture in Maynooth from 1200 (the founding of the castle) to 1795 (the founding of St. Patrick’s College).

Jp.

17th May, 2025.